Growing up, Ben Lovett never particularly considered himself a horror fan. He just liked good stories and didn’t really gravitate toward a single genre — of film or music.

So it’s merely a coincidence that Lovett, now a respected singer-songwriter, producer, and film composer, has carved out a niche for himself in the realm of genre films, often working with directors David Bruckner, Jacob Gentry, and Jim Cummings.

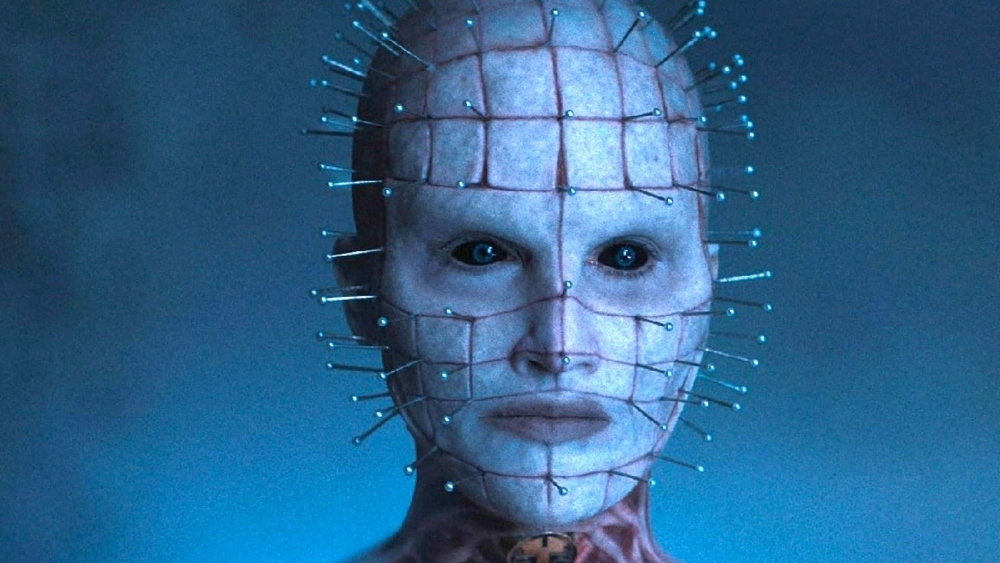

Lovett’s notable credits as a Composer include The Signal, My Super Psycho Sweet 16, The Ritual, The Wind, The Beta Test, The Wolf of Snow Hollow, The Night House, and, most recently, Hulu’s Hellraiser reboot, which Bruckner directed.

Below the Line recently chatted with Lovett, who discussed how he “stumbled” into his career, the joys and challenges of working on a new Hellraiser movie, and why he needs a vacation after such a demanding undertaking.

Below the Line: As a kid, how aware were you of the music in the movies that you saw?

Ben Lovett: I had a relationship to [music] long before I was aware of that. It was something that I was connecting and responding to, but probably in a way that I assumed everyone did; everyone sort of had a relationship to music. The seeds of that were all the usual suspects, like Star Wars, Back to the Future, Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, and all these movies in the ’80s where the music was such a huge part of the experience of the film. By the time I stumbled into doing them, I realized, ‘Oh, I’ve always loved this.’ I’ve always had an unnaturally acute relationship [with] paying attention to that stuff.

BTL: When did you realize, “Hey, I’m pretty decent at this. I might be able to make a career out of it”?

Lovett: I think the jury’s still out on both of those. I did stumble into it. It was a very haphazard start. I tried everything to convince the first people [who] were giving me opportunities to do it that it was a very bad idea, but somewhere along the way… I don’t know, maybe it changed after The Signal. When we did The Signal, it became this success story out of Atlanta.

You have this little $50,000 movie that got into Sundance and sold out the night of its premiere. We were all in our 20s, and it was like, ‘Oh, maybe we can actually do this.’ But I’m not sure. I don’t know if I ever stopped or slowed down enough to consider it as a viable career because I was always doing other things as well. I was writing songs, playing shows, and producing other artists.

BTL: All of which you’re still doing now.

Lovett: Yeah. It’s always been this thing that I feel fortunate each time I get an opportunity to do [it], because I never fully decided, pivoted, and focused [on], like, “I’m a film composer. This is what I want to do, and this is what I’m going to be all about.” Things have just happened organically. At this point, I have to admit, things continue to show up, so I must be doing something right or at least something that works for enough people that there’s a little niche, an area of it that people keep coming to me for.

BTL: It doesn’t always work out that people we work with at school or collaborate with on early projects turn out to be successful in the long run, but here you are, still collaborating with David Bruckner and Jacob Gentry nearly 20 years later…

Lovett: I consider it a real gift. It’s only when you get to this point in your life, looking back [over] that time, that you realize how rare that is. When you’re young [and] you’re starting out, you think all of your friends are geniuses, you’re all going to be doing it forever, and everyone’s going to be successful… and then time proves otherwise. Anytime that I get to saddle up with those guys again, it’s a very unique experience because of all the history and the shorthand that [has] developed between us over the years, [and] also because I realize it’s a very rare thing.

BTL: What was your initial reaction when David called you about scoring Hellraiser?

Lovett: It was exciting because it meant we had a larger sandbox to play in. It’s hard to say this the right way, but it’s more than I was excited about doing Hellraiser; I was excited about doing another project with David where we were going to have a bigger mission, and a bigger dragon to go slay. I got excited about the opportunity to go further in my collaborations with these guys, and I knew that this was going to challenge us in ways we had never run up against before.

Then you move into the “Oh, shit” of it all, realizing just how formidable an opponent this material would actually be. That quickly moved into conversations about, and really getting an education on, how, with those original films, such a big part of their identity [were] the Christopher Young scores. The relationship to the kind of music he made, for the style of films that those are and the image system of them, is part of what’s intrinsically so identifiable and unique about them. I knew it was going to be a new set of challenges we’d never dealt with.

BTL: The original Hellraiser is iconic in horror circles. Young’s score is equally iconic as well, and as you said, the heart and soul are enmeshed with the film as a whole. How did you go about walking that fine line of paying homage to Young’s score while creating something brand new that has your personal stamp on it?

Lovett: I feel like Christopher Young defined the sonic landscape of that world. Even though they’ve made so many of those films, everyone’s working in the shadow of what he originally established as the identity of Hellraiser. When you go into it, the influence of that is inescapable. Even if you’re deliberately trying to do something very different, you’re still responding to the influence of what’s been established. Our conversations were about, ‘How much of that do we emulate? How much of it do we base on what other people have done with their expressions of this material? How much do we allow ourselves the freedom to explore and reinvent?’

We knew the right answer to that was finding the right balance of those things — it needed to be both. It needed to be both for it to feel like Hellraiser to us. It needed to still capture the spirit, the quality, and the characteristics of those scores. David was always challenging me to not just strictly write in the style of another composer and not just focus on trying to make it sound and feel like the original movies; capture that, but maybe the best way to pay homage to them was to allow ourselves the freedom for our creativity. To run free with it, and find our own sound.

BTL: It surely helped that David’s take on Hellraiser is not a straight-up remake. Yes, it’s got Pinhead (Jamie Clayton) and the Cenobites, but it also introduces new characters, including the protagonist, Riley (Odessa A’zion), and, the villainous Roland Voight (Goran Visnjic). How did you approach the compositions for Pinhead and the Cenobites, since many know those characters already, and then also Riley and Voight?

Lovett: For Pinhead and the Cenobites, it felt appropriate to do something that was calling back to the thematic material that Christopher Young had established with those characters. Since we’re reinventing them, they are new interpretations of those characters, and it felt like those needed to be delivered in a style and manner that suggested that it’s evolved; it’s transformed into something new.

The way we incorporated the original theme for the Cenobites — the big, bold, brass fanfare of the Cenobite theme in Chris’ scores, that’s Doug Bradley. That’s those versions of the way those characters are presented, in those films. It just didn’t work with Jamie’s performance and the way our characters look. A lot of that came from what they did in the design of the characters, embracing the demons to some, angels to others, and leaning into the angelic side of that. There was so much of this divinity to Jamie’s performance, and it just didn’t work. When she showed up, we tried it, and it didn’t work. We knew that for the fans, and for ourselves, we wanted it to call back to that.

The evolution of those ideas led us to a lot of experimentation — trying them on different instruments and employing them in different ways. In the score, you hear that theme reprised as this insidious melody snaking around in the chorus, by a soloist. The theme is stretched out, elongated, and slowed down. The choir is doing the Penderecki-style waves of it, and then you have this one soloist moving around freely and improv-ing with it.

BTL: That was Theodosia Roussos…

Lovett: I would sing the phrase to her, and she’d sing another one. Then I would change it ever so slightly and sing it back, poorly, and she’d sing it back beautifully. It was volleying these ideas back and forth until we found something that sat in there. It felt like it was bringing out something in how Jamie delivered the character and the way the cameras captured her. It was a lot of being informed by the visuals and what was on screen. It felt more appropriate for these versions of the characters. Where Riley and Voight are concerned, those are entirely new characters, so it felt right that they needed new music — new melodies that were coming into this world fresh.

Since Roland is our conduit to that world, we meet him being very studied in and knowing all about the Cenobites, and the box. He’s on the same path Riley is on, but he’s so much further down the journey that it seems like he’s the middle ground where this is concerned. Voight has new melodies but delivered a little bit more in a style like the original films. It’s classical, Gothic, lyrical, [and] romantic, and it’s meant to feel like the way that character might’ve been treated musically in the other films.

Riley, on the other hand, just stumbles into this world and doesn’t belong there. The way the characters are represented on screen — the way they dress, the way they talk, how they live — it just seemed like they’re synths, guitars, and beats. The one connection point [between] her [and] the rest of the classic instrumentation of the score is the heart, and it’s a heart that follows Riley through the movie, but otherwise, she has a much more modern palette of instrumentation.

BTL: The score was recorded in Bratislava, London, Los Angeles, and Asheville, North Carolina, where you’re based. How often did you have a full orchestra? And how did you oversee everything? Zoom? Source Connect?

Lovett: Almost all of it was recorded remotely. I did all the Asheville stuff in person, but the restraints of the production schedule just meant that I had to… with a lot of this stuff, the logistics sometimes guide the creative in such a way that you have to find creative solutions to get what you want. Some of that was recording in these different places and breaking it up so that I could do things on the same day, back to back, and be in a bunch of different places in a compressed amount of time.

Source Connect connects to Pro Tools and acts as a real-time, Zoom-like interface, where I can see the conductor and a shot of the musicians. I’m communicating with him in his earpiece while they’re doing the takes, and it’s being fed through the console, so I’m getting a real-time, high-quality, full version of what they’re recording. I’m giving them notes, just like we’re talking now. It’s not the ideal way to do it, but it’s a way.

BTL: Do you think that is the future? Or do you hope to be in a room with a 50-piece orchestra again at some point?

Lovett: The answer is “yes” to both questions. People were starting to do more of that prior to the onset of the pandemic, and it’s only ratcheted up since then to where it’s become the default method for a lot of non-union things where you have to find other locations to go record. As someone [who] has such a background in a current occupation of being in the room with musicians, recording bands, and studios, I like to be in the room.

It’s a different energy when I can run in there and go, ‘Everybody, wait! Let’s do it one more time. You guys do this…’ There’s a lot that you can communicate better. While it’s a way to get it done, you have a note and you’re telling someone who’s telling other musicians over a thing, and they don’t speak English, so it’s not a perfect solution. But they’re all professionals, and they’re all fantastically talented musicians. If you’ve done all your prep and homework, you can get it done.

BTL: When you are looking at an image and somebody is screaming their brains out, where does the music fit in with that? Are you trying to amplify the scream? Are you complementing the scream? Do you want the music to be heard over the scream, or let the scream be heard over the music?

Lovett: For me, it is entirely driven or guided by where we are in the story at that point, and who we’re with in the moment, because sometimes we’re not necessarily emotionally with the person who is screaming. We might be with the person who cares about the person who is screaming. I find that the job is often to communicate the part of the story that you can’t shoot and you can’t put in the script. You can’t have an actor say it, but we need to feel it. We need to understand it. Music is probably the best way for us to process it, in a way that we process human experience and emotions.

Sometimes, just to use that example, in particular, it’s like it’s already being covered. We understand that this screamer is in pain, and they’re in danger, so what else do we need to communicate? I feel like no one’s having any trouble getting that part of it, but sometimes they may need a little help. The director will be like, ‘Can you ramp it up a little here? I didn’t get the best scream,’ or ‘I didn’t get the best out of the actor,’ or ‘We didn’t get the coverage to really get the best shot of this. It’s supposed to feel a lot more intense than what we’re able to get in camera.’ In that case, it’s like, ‘Alright, let me turn the screws on you, then.” It may be a moment that is not fixing or improving something that isn’t working, but taking it up a little bit of a notch.

[An example] would be the Nora (Aoife Hinds) scene, when Pinhead has Nora strung out, loop-style, upside down. That was a moment where I knew that music can really help us feel the, “Oh, God!” of that. There’s a lot in the score there. It’s not musical at all, it’s just a way of using notes and sound to draw out an emotion and a response.

BTL: What else are you working on?

Lovett: I am working on going on vacation. I’m trying to take a little break after Hellraiser because it was about nine or 10 months straight for me. It was the longest… top to bottom, seven days a week, just going at it like crazy. It was the biggest. It was 97 minutes of score that I had to write, perform, and produce. So, I’m looking to catch my breath a little after this. My songwriting, in that part of an artist’s career, had to hang out on the sideline for a minute while I’ve been jumping from movie to movie, and I’m looking forward to picking up the guitar, writing a few songs, and making sure I still know how to do that.

BTL: Let’s say the phone rings and David Bruckner says, “We’re doing Hellraiser 2.” How ready are you to return to that world?

Lovett: Not if it’s starting tomorrow! Let me come back from vacation and then we’ll worry about it. Ask me on the other side of it…

Hellraiser is now streaming on Hulu.