It is the time of year for arbitrary lists and making one of the “top” movies of the year is a tried and true one. But “top” implies seeing them all and ranking, a task not even the most dedicated of critics can claim to achieve. Instead, I’d rather mention my favorite ten movies of the 200 or so I did see in 2021.

2021 was in some ways a banner year for film. With so many movies held back during the first year of the pandemic, particularly for tech-driven pictures whose directors understandable tried to get audiences to see their work on the big screen—the persistence of COVID and Tenet’s 2020 approach notwithstanding. Some of the interesting movies of the year came from seasoned directors – Pablo Larrain, Ridley Scott (The Last Duel), Wes Anderson, Guillermo del Toro, and Joe Wright come to mind – although the year also augured the first offerings by actors turned directors that show a lot of promise, including Maggie Gyllenhaal and Rebecca Hall. In the end, some of the best movies I saw in this calendar year came from a mix of tech-oriented and script-oriented films, veteran and newer auteurs, and U.S. as well as non-U.S. markets. And, given that it was another productive year for Timothée Chalamet, it is no wonder he showed up twice on my top ten list. Another, far less known but perhaps equally as talented Norwegian actor did as well.

In other ways, though, 2021 was either a catastrophic or at a minimum watershed moment for the movie industry. Are movies in theaters dead, save for big event movies like Spider-Man? It sure seems that way. You cannot argue that COVID kept people away from audiences when they went in droves in the middle of a surge to see the Marvel film. Martin Scorsese’s prediction, about the inhospitability of the current film industry to art and creative, rings terrifyingly true.

10. Dune

Denis Villeneuve’s space opera is perhaps the technical masterpiece of 2021 and the only one on the list that did anything at all at the box office. The film fires on all crafts cylinders from makeup, cinematography, costumes, and art direction. It helps tremendously that it features career best performance for the surging Timothée Chalamet and Rebecca Ferguson, at the center of a maelstrom of a story that leaves viewers anxious for more. Ultimately, however, Dune is a triumph not only because it’s well-made, visually appealing, or fundamentally intriguing. The movie effectively reminds us of the power of the big screen, of the effect that effects can have on an audience, and of the reality that—despite modern audience’s rejection of the experience and preference for the streaming—watching a movie at home simply does not and cannot compare to the theatrical experience.

9. C’mon C’mon

Mike Mills closed out his trilogy about humanity with the best chapter since Beginners, with a story about a middled-aged man (Joaquin Phoenix) developing an unexpected bond with his young nephew (Woody Norman). Told in beautifully bold black and white cinematography, the contemplative, humanistic elements of the movie offer both sorrow and hope for the future, through the eyes of the aging and of the innocent, and reminds us of the beauty of complex yet simple interpersonal relationships. This type of quiet, more somber performance is what makes Phoenix such a uniquely talented actor, the more bombastic, stagey roles for which he receives awards notwithstanding.

8. Prayers for the Stolen

Mexico’s submission to the Academy Awards is as urgent and poignant as any film the country has submitted to the Oscars this side of 2010. Focused on a group of mothers that live in a remote, countryside village, the film exposes the god awful truth behind the terror that cartels run amok inflict on villagers and young women in particular. Buoyed by a moody, somber yet colorful cinematography and naturalistic acting, Prayers for the Stolen continues Mexico’s trend of sounding, through film, the alarm of the inequities and violence gripping certain pockets of the country, even though few—at home or abroad—seem to want to listen.

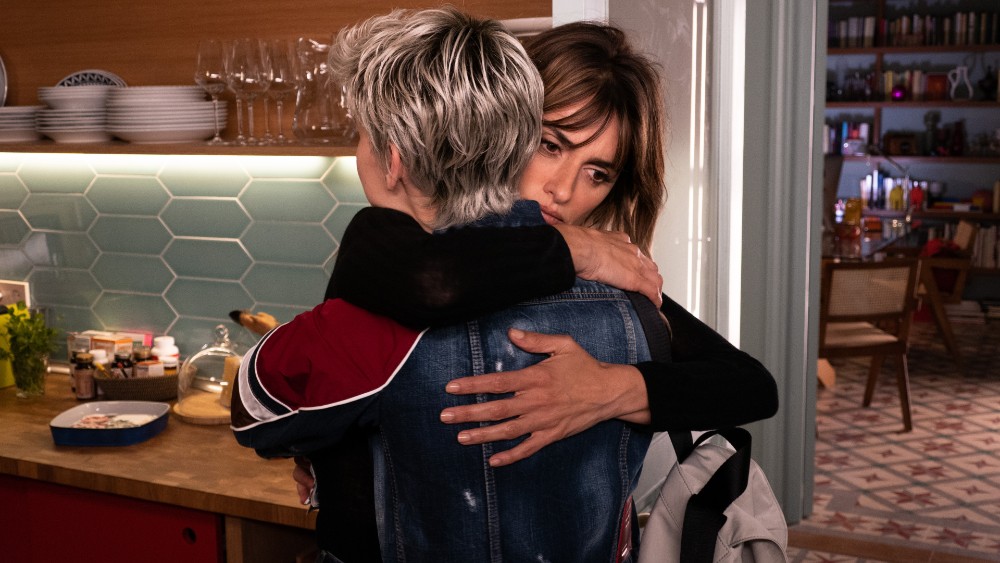

7. Parallel Mothers

Pain and Glory was Pedro Almodovar’s most personal film of his career and his best in nearly a decade, but Parallel Mothers came from the heart in a different way. Focused on Janis (Penelope Cruz) in her quest to become a mother as she settles into her middle age, the film is set against the backdrop of a modern Spanish society still struggling to come to grips with the horrors of its Civil War and the brutal totalitarian regime of Francisco Franco. The film features the impeccable and evocative art direction and set decoration that are Almodovar’s signature, another stunning performance by the Oscar-winning Cruz, and yet another important message about a country told through its Oscar selection, a theme in this and most year’s Best International Feature Oscar race that the Academy typically has no interest in going for.

6. Bergman Island

Mia Hansen-Love returns to the big screen with a film that is not only about film—though it is very much that, as it focuses on legendary filmmaker Ingmar Bergman—but, most importantly, about what film and storytelling can mean to a person and their life. Vicky Krieps and Norwegian actor Anders Danielsen Lie star and give a masterclass in acting, but it is ultimately Hansen-Love’s original screenplay, a love poem to movies and the creative process itself in the least possible corniest of ways, that makes this one of the best films of the year (despite its light tech touch). Through the story of a woman working on a film while trying to find inspiration in a remote island Bergman called home, Hansen-Love creates a multilayered analysis of immersion, inspiration, and creation as they relate to any work of art. The writer becomes the written, fiction becomes truth, and truth becomes fiction in subtle but emotionally powerful ways.

5. Drive My Car

Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s film about life, death, and art may well win Japan an International Film Oscar next year—if voters can handle its three hours. The story focuses on a theater actor married to a film screenwriter, with a shared bond over their storytelling interests, until tragedy sets them apart. The theater actor embarks on a project that is purportedly meant to distract him but puts him on a collision course with his demons, through the eyes of one of the actors he casts to play in Chekov’s and of the lower income driver that is hired to take him around town. Ultimately, the film is about regret, self-acceptance, and past traumas that define us. Hamaguchi’s imposing, steady camera, always focused on his actors’ emotions, makes Drive My Car stick with you—as bizarre as it is sometimes—also in part because it seems so plausible. Though there are a few interesting cinematographic choices during a sequence towards the film’s end, set in the Japanese countryside, this is not a tech-heavy film, and it relies instead on a hearty script and powerful acting.

One of my biggest fears going into 2020—and then frustratingly extending into 2021—was Steven Spielberg’s take on the iconic Broadway musical West Side Story. (Don’t call it a remake of the Oscar-winning 1961 film.) But the fears were unfounded and perhaps misguided from the get-go. The source material remains as powerful as ever, and Spielberg’s unique, majestic directorial touch remains unblemished. The film scores high marks from start to finish, from script to craft. Tony Kushner changes the lines in subtle but powerful ways that speak volumes about the undercurrents of classism, racism, and youth anxiety that are the motifs of the original. Justin Peck modernizes the choreography while paying homage to and respecting the original. Adam Stockhausen’s production design is on full display thanks to gorgeously colorful cinematography by longtime Spielberg collaborator Janusz Kaminski. And Spielberg amassed a cadre of young talent—this time with actual, impressive singing to go along with the dancing—that includes Ansel Elgort and Rachel Zegler in the lead roles, though the credit really goes to Ariana DeBose and Mike Faist and their stunning portrayals of Anita and Riff, respectively. And what to say of the new character embodied with unending freshness by the legendary Rita Moreno, whose unique performance could lead the actress to yet another cadre of impressive awards.

3. The Worst Person in the World

Joachim Trier (Thelma) returns to the big screen with the supposed completion of his “Oslo Trilogy,” with this subtly seductive film that focuses on Julie, a self-involved millennial played by an impressive Renate Reinsve. The film is told in several chapters that focus on a few years in Julie’s life, as she navigates love, career, family, and, most importantly, freedom. Trier’s point is that unabashed freedom—freedom from responsibility, particularly to others—can be a two-edged sword, and that our modern society’s obsession with id can be startlingly destructive. Anders Danielsen Lie plays Aksel, one of the many people in Julie’s life that she does not fully appreciate or even respect, all in the quest to find herself, to make herself happy. Julie, however, is not a loathed character—how can she be, when she is so witty, charming, and, ultimately, hapless? Julie becomes, instead, a symbol of Millennials, or maybe of Gen Z-ers, or perhaps of all modern European society. Though so much in European film this side of 2000 tends to focus on the anxiety of the white, old, patriarchy, of the aging men—and, certainly, films that get submitted for Oscar from Europe tend to almost exclusively focus on that—it is refreshing to see Trier and Norway cast their anxieties at the younger generations.

Jane Campion’s adaptation of the 1950s Western novel is, perhaps more objectively, the Best Picture this year. The movie focuses on a pair of ranch-hand brothers (Benedict Cumberbatch and Jesse Plemons) in 1920s Montana, and how their lives are disrupted when a sorrowful widow (Kirsten Dunst) and her odd son (Kodi Smit-McPhee) crash their party. This Netflix film has it all, including majestic, broad cinematography by Ari Wegner, a powerful score by Jonny Greenwood, meticulous and thoughtful cinematography by Grant Major (Oscar winner for The Lord of the Rings), and of course careful, methodical, and alright masterful direction and an adapted screenplay by Campion herself. The story she tells unfolds slowly and deliberately, focusing on different darkness that can motivate or crush the human spirit, the cruelty and evil that people can impose on each other, and the loneliness and sadness of the American West. Benedict Cumberbatch and Kirsten Dunst give career best performances as two variously troubled souls, though it is Smit-McPhee who ultimately steals the show with a bone-chilling turn as a somewhat troubled teenager. With her return to the big screen after a few years in TV land, Campion, only the second woman ever nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director and the most likely winner of that prize this year, cements her legend as one of our time’s great filmmakers.

1. Don’t Look Up

While Jane Campion’s film is objectively the best or one of this year’s best, Adam McKay’s end of the world doomsday parody—also on Netflix this coming Friday —is unquestionably the most important. McKay’s original story focuses on two scientists, played with dedication and gusto by Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence, who discover a life-extinguishing asteroid headed towards Earth. Over the course of the next several months, the duo must struggle against a cadre of obstacles to get humanity to pay attention to the existential threat. Along the way, they encounter a self-serving, egomaniacal President played by Meryl Streep, only interested in ratings, votes, and, ultimately, herself; a media that is only interested in ratings as well, but also in easy bits and faux entertainment, as personified by two morning show anchors played by a stupendous Cate Blanchett and Tyler Perry; and a populace that is stupefied, also disinterested in few things other than ratings, memes, and the hot thing of the moment. The film is anchored by an amusing and powerful song performed by Ariana Grande and also stars—who else?—Timothée Chalamet, whose character stands in for disaffected, disinterested youth. McKay’s script may be heavy-handed, and you can certainly accuse him of trying to bite off too many pieces of critique of our modern polity. But the end result is a picture that is hilarious, terrifying, sad, and as urgent as urgent can be. The irony, of course, will be that it’s difficult and uncomfortable message, its unforgiving satire of everyone involved, from the critics reviewing it to the audiences watching it, will likely make it irrelevant. But that does not mean that we are any less in peril than McKay knows us to be, and that 2021 could mark another year of humanity willingly careening into the abyss.