James Cameron‘s long-awaited sequel, Avatar: The Way of Water, is not just an enormous global box office phenomenon, but it’s also one of the finest displays of the use of visual effects and new technology in filmmaking in over a decade. As with the 2009 Avatar, it’s the collaborative efforts of Cameron’s own Lightstorm Entertainment, Inc. (LEI) with Wētā FX that helped bring to life new areas on Pandora and its creatures, as well as the new Na’Vi characters.

In the sequel, Sam Worthington‘s Jake Sully and Zoe Saldana‘s Neytiri have created an extended family, which includes teenager Kiri, the daughter of Sigourney Weaver‘s Grace, who is also portrayed by Weaver. The return of Stephen Lang’s Colonel Miles Quaritch in the body of a Na’vi recom (short for recombinant) drives the Sullys from their home in the jungle to the reef home of the Metkayina, a water-based community of Na’Vi that take the Sullys in, only to have their own home put into danger.

To create a visual effects-heavy film like Avatar: The Way of Water, it takes an army, and Below the Line got to speak to three VFX powerhouses, including the film’s two Senior VFX Supervisors, Joe Letteri and Eric Saindon, and Senior Animation Supervisor, Dan Barrett. Letteri has won four Oscars – including one for technical achievement – with six more visual effects nominations beyond that. Saindon shared Letteri’s Oscar nominations for two of Peter Jackson‘s The Hobbit movies, while Barrett has been nominated for three Oscars in visual effects, all three of them for Planet of the Apes movies, shared with Letteri.

Below is a rather lengthy and detailed interview Below the Line did with the trio from Wētā FX shortly before Avatar: The Way of Water was released.

Below the Line: I’ve spoken to a bunch of people at Weta FX over the years, and I know it’s uncommon for a single FX house to work on an entire movie, so is it true that Avatar was completely Weta FX, or were there other places?

Joe Letteri: Actually, in the end, ILM had to take about 100 or so shots. We just hit our limit of what we could get done. So yeah, we broke up one sequence that they took. By and large, I always like to work that way. You don’t have your camera broken off into several camera departments, right, even though you might have multiple units. I’ve always felt that’s the best way to work, and we’ve got this relationship with Lightstorm that goes back to the first film. Right after we finished the first film, we sat down for what Jim called a “mid-mortem,” because it wasn’t a post-mortem, ’cause there were more films coming, just to talk about what we would do next time and to start planning for it. Everything was spun up on the last film, kind of as needed. Lightstorm got going, and we were in, trying to help them get everything going. They had their thing set up, and we had ours, and we were passing information back and forth. We just thought, ‘this needs to be integrated.’ That was the big thing that we did. We’ve been working on software ever since then, to integrate our two facilities so that they’re doing everything in a live-action or real-time context, so Jim could shoot his virtual cameras. You’ve essentially got lower-res assets and fast interactive lighting and capture going on, and virtual camera. Jim could see everything like it was going on live on stage, and that’s integrated right into our system. That feeds into the high-res assets and everything that starts going into shots. We had this two-way system where we can build assets and get them to them, that they can use on the stage. They can get the results of what they do on the stage to us. It’s been highly integrated.

It sort of made sense for us to just take on the whole thing and do as much as we can, especially because of all the character work. The characters are everywhere in this film, and that kind of stuff is hard to break out. As Dan will tell you, it’s all about casting. We tried to put a team together who really understood what the actors were doing, and how that would translate to the character performances. That’s really what held it together. The one sequence that we did carve off was the Manifest Destiny, the spaceship, coming down, that didn’t have any of the character work. That was really the only one we could carve off. I think Dan could speak more to the casting aspect of it.

BTL: Before you jump in, Dan, when you said that you had a “mid-mortem” was that after the movie had come out and was already in theaters or was that even before that?

Letteri: That was several months after the movie had come out. That was [the] middle of 2010 if I remember correctly.

BTL: Dan, when did you get involved? I’m sure Joe was there at the very beginning, and I’m not sure if that was that conversation you mentioned or more recently?

Letteri: Basically, we never stopped since the last film. There’s just been ongoing work with Lightstorm to get prepped. As the art department got going, we were receiving designs, we were doing motion tests. We were working the whole time, plus we were doing a lot of software development, pieces of which we incorporated into our pipeline, our toolkit. They got used on other films. We roped Peter [Jackson] into being a guinea pig for us, for testing the next iteration of the virtual camera that he used on Hobbit. We just tried to keep everything moving as much as possible, because we needed it for all those films. Also, we knew we were going to need it for what was coming in this film, even though we didn’t know what it was. We knew we were gonna need a lot.

Dan Barrett: I was lead animator on the first film, but then in between films, I have been doing a few other things. I worked on this film for about four and a half years. Back to Joe’s point, it is so important, not only for the importance of the new facial tech for the film and for the work that you see, but also just for our team’s understanding the characters, as he said, and also just to understand story really well. I think that’s really important for an animator to know what it is you’re doing, to make sure that you’re getting it all right, and helping to tell the story. When it’s not broken up, and you’re not getting an opportunity to perhaps see a cut as a work in progress, having all the shots in-house – or at least the lion’s share of the shots in-house – is a luxury and not necessarily a necessity, but certainly something that’s of great benefit. I personally like it when we get to do the whole thing; it’s a great luxury.

Eric Saindon: The consistency of character really is a huge benefit to keep it all in-house, too. It just helps with the characters, like you get consistent translation of the performance on the characters, which really makes a huge difference.

BTL: I have spoken to a couple of other Weta FX people about the tech used for The Way of Water, but what was the first step? I assume you were already developing the tech even before Jim had completed a script?

Letteri: We were, because we knew, in general terms, coming off the last film. Really, the way films have been going, mostly the last few years, you have to be able to do anything. Once you’re on a new planet, you could get hit with anything, whether it’s clouds, water, a river, someone falling in the dirt, character performance, flying … In general terms, we started planning for all of those things. But really, when we read the script about five or six years ago, that really started to focus in on exactly what we’re going to need.

BTL: Had the art department already been working on designing locations and some of the creatures involved?

Letteri: I think Jim had an art department up and running, and they were going in parallel with the development he was doing with the story team, with the scriptwriters. He was feeding them ideas as they were writing them, and they were coming up with artwork in parallel. Again, that really helped us, because by the time we got versions of the script that Jim was happy with, we could walk through the art department and see the story laid out in picture form.

BTL: Eric, I know you’ve been working on other things besides Avatar, but what part of the VFX were you focused on?

Saindon: Luckily for me, the project I was doing in between, I mean, Green Knight was just a little one, but we did Alita: Battle Angel, and that was using a lot of the same tech that we were then developing for Avatar, which is really helpful because it was all LEI. It was using a lot of the same processes. A lot of it was earlier versions of it, but it was a great point to try some of this new tech and use it in an actual shot context. Battle Angel was one of the big ones I worked on in between, and then obviously, Green Knight just sort of slotted in there a little bit.

BTL: Getting back to animation, Avatar really upped the game on performance capture, even though Peter had used it for Gollum and King Kong. Avatar had a lot more characters at once, and The Way of Water has even more than that with fewer humans. As animators, do you always rely on what was done with the mocap on stage, or do you have to change things to make them work within the context of other CG-only characters?

Barrett: In terms of the stuff we reworked on this film, that was limited to stunt work, maybe stuff that couldn’t be done. Jim’s a great director for performance capture. He understands it, and there’s a faith that he engenders in the cast and the process, so they definitely committed to the process. In most cases, what we’re doing is we’re bringing through exactly what it was the actors gave him on the day. It’s not often that we’re going in there and changing things. Our role there is to ensure that we’re seeing everything that’s being given by the actor, and that’s right down to the most subtle things and making sure that we bring that through. Occasionally, there are things that we do get in there on, but it’s not dramatic performance — it’s [a] more physical performance that we’re going [for] there. We’re not looking for cartoonish poses, anything like that. We are making sure that the performances come through. Occasionally, there’s a bit of translation required. These are bipedal characters on the whole, so they’re humanoid, so that the transfer from one to the other is pretty seamless, slightly different proportions. When it comes to facial, there’s a little bit more required, in terms of interpreting how a face moves on the actor, as opposed to on the Na’vi or the Recom. The way that the facial models are designed is that there’s a lot taken from the actor and put into the model.

Probably, for us, in terms of the facial, the biggest challenges were Kiri and Quaritch, where we have actors that are considerably older than the parts they’re playing. While their faces look a lot like their younger selves, they are being acted on older faces, so there’s a little bit of translation required there. Once we had that laid down, it was just us bringing the performance through. I have a team that dedicates their lives to looking for the kind of details that audiences don’t see, but that audiences feel. That’s what we trade in, making sure that we get it all.

Letteri: The other area that is actually key in all this was the underwater performance capture, because the actors would spend, like, a minute or two underwater on each take. When you’re working all day like that, they’re wearing goggles and nose clips, and they’ve got a single camera on their face. You can’t really count that as performance. You can get some idea of the performance, but you can’t get the detail. What Jim would have them do is after the take, they would come up, put on a normal head rig and reperform dry, so that we had their facial performance there. Inevitably, that never times exactly with what the underwater body is doing, as good as an actor is with that kind of muscle memory, it’s never one-to-one. That’s where the animators really have to take the interpretation — understand the character, understand what that actor is doing underwater, what they did as soon as they got out of the water, and how to match the two. That involves subtle retiming, so that it fits the motion, eye directions that are coordinated with a head turn, lots of little things that make it come together as a real physical performance.

BTL: I know some animation houses like DreamWorks will have specific animators on specific characters to keep them consistent. Does Weta do that by finding animators who are really good at certain characters and can focus on them?

Barrett: To a certain extent. The extent to which we did that was more about understanding the rig, working with modelers on the rigs, being a point of contact for the rigs. The difference that we have, in this case, as opposed to say something like DreamWorks, is where you have animators who are also the actors. You’re looking for a lot more consistency in that way. On a film, when you’re doing performance capture, like we’ve done here on Avatar, obviously the performances are driven by the actors, so you have that consistent thread going through the film, and there’s that guidance there. We certainly had people that were experts in characters, but that was less about performance and more about certain slightly more technical aspects of the rigs.

Letteri: Some of that would come [down] to how the work is broken down. We’ve never taken that approach. We’ve always said the animators, especially the animation leads and supervisors, need to understand the sequence that they’re working on, getting back to what Dan was talking about story. Characters can come and go in those sequences, and they have to understand how to make it all work. But having said that, some animators will get sequences that are mostly in the jungle, and some animators will get sequences that are mostly in the Metkayina village. Due to that, they’ll have a slightly different focus. It really helps us to have animators be able to understand all the characters, so that the story makes more sense.

Saindon: Another huge thing with this — because you were talking about background characters compared to the first film and this film. One of the huge differences for me, and especially watching the film, was the new facial system that Joe really pushed and developed for this film made such a huge difference. [In] the first film, you saw Jake, you saw Neytiri — they looked great, their facial was great, but the background characters were a little less so. And then you watch this film, and honestly, you could watch every single background character, and you get a great, amazing performance out of every single character in the background. A lot of that is really due to the new system that Joe helped develop and really push forward. I think it made all the difference in the world for this film.

BTL: I’m glad you brought up facial capture, since that was my next question. I know you developed this on the first Avatar and on the Apes movies, but do you have enough of these rigs that you can have ten to twelve actors using them all at the same time?

Letteri: Well, there are two aspects to it. There’s the capture, which has developed, and yes, we had multiple actors being captured on set. We went to a stereo camera set-up for this film, because the cameras are now small enough and lightweight enough that we felt that would work. In the past, you’ve probably seen there have been like four-camera setups, even that have been used by other facilities. We’ve always not done that; we’ve gone for the lightest weight possible, just to make the actors as comfortable as possible. But this time, the cameras were small enough that we could get away with a stereo camera pair. But the facial animation system that Eric was referring to and that Dan mentioned earlier, was something completely new that we wrote and developed just for this film. It wasn’t even available to us on Alita. It was something that we developed and are using for the first time here. The idea there was to rather than using a traditional system where you’re looking at the shapes of the face and trying to blend between them, we developed a neural network that understands what your muscles are doing under the skin to produce the expressions that we see. We could use that as a better way to translate from actors’ performances to the character performances.

Barrett: One thing Weta has done for many years is we’ve been good at delivering emotionally-plausible performances. I think when you look back at Avatar, you can see that, but I think there are some areas that certainly bugged Jim, and there are some areas where we perhaps weren’t as anatomically-plausible. This new system delivered in spades on that, not only as a solver, but also as an animation tool that essentially kept the face within a plausible space, a space that the actor’s face could go to, for instance. Some of the old systems that we’ve used, it was really down to the animator being very careful about the way they went about things. It was very easy to get off track. It was a remarkable new system that we had on this film, and one that we’ve really enjoyed using, and I think one that shows results.

BTL: There must have been a water tank involved, and is there still a lot of green screen, and is there stuff being built? What was on set that you were sending to the folks back on Weta?

Saindon: It was all over the place, to be honest. I think the final number was 120 odd set builds, and a lot of those were obviously green screens for Spider, because we have a lot of Spider shots on green screens or with very minor sets, like logs or things like that. There’s also some very, very large sets. The Atwell deck for the Sea Dragon, which is like the center of the Sea Dragon, was an entire soundstage, from front to back with two full-size boats in there, the Picador and the Matador. There were several very, very large sets, which is great because we were able to get the actual humans in live action. When we had a set where the majority of it was a live-action or a human-based element, we could actually get the interaction there and add our elements to it. To be honest, I think the best part of that whole thing is Jim, he built all of these sets in the virtual. The production designers built all the sets, the Sea Dragon, all these other sets, and then the live-action set was built, honestly, very, very close to the digital version. When we did simulcam, you really couldn’t tell what was live action and what was CG, because we had simulcam set up for every shot. With new live depth-compositing we used on set, we can get proper layering of characters and CG onto the set. You got a very good version of whatever live-action set you were going to use, and Jim was able to set composition, set eyelines, and set all these things very accurately and very precisely for each shot.

The depth-compositing is something new we did for this film, too. That really allowed us to see our live-action characters and CG interacting at the proper layer. When Quaritch goes in front of Spider and then goes around and goes behind him, with depth-compositing, you’re able to actually see that happen and know that the eyeline from Spider or the interaction from Spider to Quarritch was going to work, because you could see it in real-time.

BTL: That’s a great segue because I wanted to ask you about Spider and about depth-compositing. Spider is an interesting part of the mix because he is an all-human character often fully surrounded by visual effects. How are you dealing with the young actor playing Spider?

Saindon: Well, Jack [Champion] was great. Jack did all the performance-capture beforehand, so he went through the whole films, did all the performance-capture before he actually had to do the live-action. He knew all these scenes. He knew all the interaction with the other characters, and he did it with the actual performance. He did it with Sigourney, he did it with Zoe and Sam. When we got to the live-action bit, he became a very seasoned performer, because he had done the whole film, or the first two films really, and then the live-action element, he was able to call upon what he had already done, plus we had the eyeline system — it’s essentially an eyeline system from sporting events. It’s a fly on the wire monitor, and it put it at the right height, it put it in the right location, and we had a face on it for whoever he was talking to. If he was talking to Quaritch, it had Stephen Lang‘s face on there with the performance, so Jack could actually interact with Lang at the right height and right timing and get it all to work. Jack, because he went through this whole process and understood it all, and the way he was able to act it out the first time through where you didn’t have to worry about cameras, it was more of a theatrical performance. He knew the scene pretty well, and how they should work, so he was a great asset to have on the film.

Barrett: All of that planning, the Spider cam with the facial performance, the eyeline camera, all of that stuff, just made our lives in animation so much easier. There’s nothing worse than seeing a plate that obviously the director is very attached to and realizing that you just can’t do what was expected, and you have to start making compromises. Every plate that we got, everything just dropped in beautifully. The eye lines all worked, and I think it’s a testament to a big team that worked on that shoot on how successful it was.

BTL: Joe, do you want to tackle depth-compositing?

Letteri: Okay, so this goes back to old-school compositing, sort of Photoshop style. The way we used to do things is you’d build a layer for compositing. That’s what green screen is, or blue screen. You have your character, you pull them off and you say, “Okay, now you’re in front of this background layer.” So, you have foreground, background, foreground, background, we’ve done a ton of films that way. Even the first Lord of the Rings series was done that way. It becomes difficult the more and more elements you create, and the more integration you’d need to make that work. The best example is, like Eric was saying, say you’ve got a tree, and you need an actor to walk around the tree, and it’s a virtual tree. There’s no single layer that works anymore. Or the other way around. If you’ve got a character walking around actors, like suddenly, there is no AB layer that you can easily do. Back on the first Avatar film, we created a system for compositing the final shots, that was actually used as… rather than going [with] planes and planes of images, every pixel had its own depth and space. So you think about every image now everything could go in front or back, depending on where it is in space. That allowed us to do the stereo composites for the first film, and that technique we’ve been using on every film since then, I think it’s pretty much an industry standard now to do it that way.

Fast-forward to we’re shooting with this virtual camera, and Jim wants to take that live and see what the integration looks like. You’ve now got a set, and you’ve got an actor on the set, and the actor, say it’s Quaritch, needs to walk around Spider. Sometimes, he’s in front, sometimes he’s behind. How do you do that? You still want this per-pixel depth, but you need it in real-time. What we did was, we wrote a neural network that could analyze the images. We put a small set of stereo cameras on the main camera to help analyze the images that the camera was seeing. We wrote a neural network then that was trained to extract that information and build this on the fly. When Jim is shooting, he or whoever is operating, could see live in their monitor the character integrated with perfect depth. Background sets, foreground objects, characters, anything, didn’t matter what it was, it could all appear at the correct depth plane, so it’s very close to what the final comp is going to look like, at least for allowing you to compose the elements.

BTL: Dan, I want to bring you back into the conversation to talk about the underwater creatures, of which we see some new ones in this movie. At what point are you and your team working with design and development to determine how these creatures will move? I know Weta does a lot of research into real-life animals, so when in the production process are you doing that stuff?

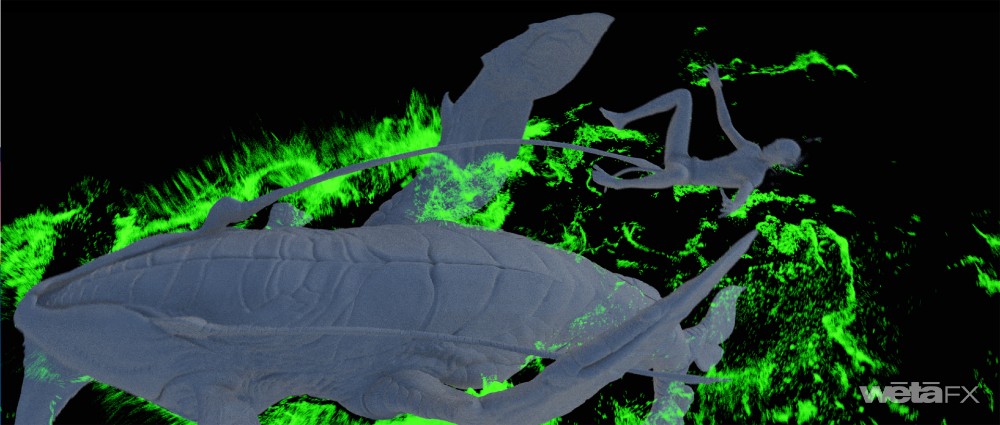

Barrett: We’re very early in the process, because a lot of the work that we did, went back to the lab, went back to Lightstorm, for them to essentially create the movie in a previs fashion, to create the templates for all of the shots. A lot of those creature cycles were done at Weta in Wellington, and then, sent back to the lab for them to use in shots. I guess, five or six years ago, we would have been working on that kind of thing, looking at creatures. One of the things about the creatures you see on Pandora is that the work that goes into the design of them is so thorough. Jim doesn’t allow anything to walk or fly that couldn’t walk or fly. A lot of the times when you get a creature, it’s been so well thought through that the way it’s going to move is almost written in its physique in some way. There are certainly creatures that Jim had certain ideas on the way that they can move. If you take a creature like the Tulkun, for instance, its tale can move like a whale, but it can also very happily swim like a shark, with its tail moving like a shark’s would. Obviously, the extra fins and legs and things that we see, but if you take a creature like the Skimwing, we were looking very closely at reference of flying fish, as well as billfish and sailfish for how they move underwater. But yes, that’s a flying fish, essentially, so [they’re] fun creatures to animate, logical creatures to animate. I’m a big fan of the Ilu. It’s sort of like the puppies and the dogs of the Metkayina people, great animals to have domesticated and a really fun one to animate.

Letteri: We’ve always approached creature design as going hand-in-hand with motion studies. That goes back to the first Avatar. We’ve always worked that way. Obviously, we had Richie Baneham at LEI, and Richie comes from being an animation supervisor himself. And also Eric Reynolds, who was our Animation Supe, embedded with LEI for a lot of what was going on with the template. All these designs, as Dan was saying, they work because as they’re being drawn up, we’re doing model tests and motion tests just to make sure that they work, that the flippers don’t intersect with the body if they need to do like a deep power stroke or things like that. All these little adjustments are happening as we go so that by the time they’re passed in for full animation, most of that has already been worked out.

BTL: What are the actors interacting with when they are riding some of those underwater seahorses, and things like that?

Barrett: It depends. It’s a bit of everything. Underwater, they’ve got rigs that can move and that can drag them through the water. Above water, for riding, there’ll be on bucks that are moving. One of my favorite bits of reference from on-set was this fantastic puppeteered Ilu head that was built for Tuk to interact with. It was really well puppeteered and was really lifelike, and Trinity [Jo-Li Bliss] gives us [a] wonderful reaction to this puppet. She was a youngster then, so I think a lot of that performance was down to this fantastic puppet that they have and the wonderful puppeteering of it. There’s a variety of things used, but it’s a little bit of a tricky one with the underwater stuff. We get a lot of great motion, but unless it’s done exactly right, we’re going to have to change it. In many cases, we get a lot of great reference to how a body moves underwater, and then have to adapt their performance to the creature later. It’s the same with flying creatures as well. You can do what you can on set, but if Jim wants to change things later, then you just have to make that rider conform. Keep the performance of the actor, but make the physicality of them conform to what the creature is driving.

BTL: I’m sure many of the actors were younger kids, which does add a whole other layer of getting them used to the technology since they don’t have the experience of someone like Sigourney to imagine stuff.

Barrett: It’s funny, because I’ve seen some photographs from the red carpet of them recently, and I don’t recognize them, because we were looking at kids. Even seeing Jack/Spider and how much he grew in the process of making these films, but strong performances across the board. There’s some amazing work from some really young kids.

Saindon: In the two years we were shooting with Jack — I mean, on and off for two years, but he went from five-foot-eight, I think, when we started shooting to six-foot-two, by the time we were done, so he shot way up. I saw him on the red carpet in London, and he’s taller than that now, so he’s just a big young man. It’s funny watching the original performance capture where he’s just a little 12-year-old kid, and now he’s a young full-size man.

BTL: Joe, Weta’s been at the forefront of the performance capture and making that part of the filmmaking process, with Peter and Jim and Andy Serkis really pushing its limits. Have you found many other filmmakers have become more open to it, as it’s currently in use now? I feel like you have these few filmmakers who do tell us a lot and others who don’t use it at all.

Letteri: We’ve done two films with Steven Spielberg that way —Tintin and The BFG. Steven was completely open to it. Obviously, Matt Reeves, when we did the Planet of the Apes films. I mean, if you’ve got the right character for it, it makes sense. Marvel picked up on it for Thanos – they were open to doing it that way. I think if you’re trying to create a character that really has some kind of empathy or human-like emotion and interaction, but it’s not a human character, it’s a great way to go, because it allows you to use the actors as the basis for the character. That’s really important, because that’s the drama, right? Animators are great, but animators have to think in a different sort of timeframe when they’re animating a character. Whereas when you’re an actor, you’re responding in the moment, that’s what acting is all about, that’s what the training is all about. You kind of want the best of both worlds. You want the actors to give you that performance and that drama, and then you want the animation team to be able to take the time to think about how that should translate to the character you want to see on screen.

BTL: Before I let you guys go, IATSE just released a statement today that they were doing a study into VFX. There’s been a lot of talk lately about positions in the VFX world. As far as I know, there’s no union. Do you have any thoughts on where your craft is in the film industry in terms of unionizing?

Letteri: I don’t really know. I know there are discussions going on about that, Weta in New Zealand as well. All I can say is we try to make sure artists have the best environment to create the best work, because that’s what we do, and that’s what we all do, right? We all are still hands-on with the work that we do, and that’s important. We’re taking this as an artist-driven medium, and that’s the way we like to work. So, hopefully, that works for everyone, but more than that, I really couldn’t say.

Avatar: The Way of Water is still playing nationwide in theaters. You can read other interviews with the below-the-line talent behind the movie at the links below: