If you’ve seen Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho, you may have been at least slightly impressed by some of the more elaborate setpieces, including a few featuring Thomasin McKenzie and Anya Taylor-Joy as the former’s character Ellie is magically transported back to the London Soho district of the ‘60s where she encounters the latter’s Sandie. This happens through a number of sequences where the Soho of the ‘60s is recreated to mirror some of the films that inspired Wright to make the thriller.

There is one particular sequence within the Café de Paris nightclub where reality and fantasy merge as Ellie watches Sandie’s interaction with a club manager, played by Matt Smith, from the club’s mirrored walls. In other sequences in the film, Ellie is terrorized by the “Shadowmen,” the ghosts of men who had been murdered over the years in her Soho neighborhood.

These are two examples of the jaw-dropping visual effects overseen by VFX Supervisor Tom Proctor, working with prolific London VFX house DNEG, which helped Soho get into the recently-announced BAFTA longlist, along with seven other crafts. (Proctor and his team were just nominated for a VES award, as well.)

Below the Line spoke with Proctor a few months back about the VFX work done for Wright’s film, although if you haven’t seen Last Night in Soho yet, be warned — we do get into some slight spoiler territory when discussing plot-specific VFX. Proctor told us how important it was for his team to work closely with other departments, from production design to makeup and choreography to make the film’s complex illusions look seamless.

Below the Line: Before we get into Last Night in Soho, I’d love to know your background before getting into VFX. Did you go to school for it or computer graphics, or was it something else in that field?

Tom Proctor: No, I was studying, painting and design at the Rochester Institute of Technology in the town where I grew up. I knew some of the faculty as family friends and respected their work, so I was studying there, and I was working for Kodak. I was at a part-time job doing tech support for this compositing software that they made. I was answering phone calls from Visual Effects professionals, and I very cheekily asked one of the callers if they would be interested in interviewing me.

I was interested in transferring to the San Francisco Art Institute, and I knew their office was in the Bay Area. They said, “When you come out for your school interviews, come out to the office, pay us a visit and say ‘Hello,” so I went and visited this weird office on a Naval base in Alamada, where they were working on What Dreams May Come, a really impressive painted world effects, really innovative stuff, which they eventually would go on to win an Oscar for, and they were just starting work on a science fiction film.

I had a good interview, and I also liked the school and decided I was going to move out to San Francisco. When they called me back, they were like, “Well, we don’t do internships, but if you just want to come work here on this movie for a year and put off school, do that. So I did. I went and worked on the first Matrix, and ended up compositing the rooftop bullet time shot on that, which was a hell of a lucky break. But it was a lot of work, and it was very rewarding. I’m still good friends with a lot of those people I met there. It was quite an adventure.

BTL: How did you meet Edgar and get involved with Last Night in Soho?

Proctor: I think I was living in New Zealand when Shaun of the Dead came out, and I remember being impressed that DNeg [did] supporting visual effects. I remember when I started at DNeg being chuffed to see him coming back [there] again and again. It was a sort of familial feeling, and a sense of pride in helping kind of nurture this up-and-coming superstar of British cinema. The company was very much about wanting to have a diverse portfolio of film, so not just superhero films, but also indies and slightly offbeat films with smaller visual effects budgets, maybe, but being sure that there’s always some diversity there, so it’s not so pigeon-holed. I saw several of the other shows going to come through the building. I think I was around during Worlds End and Scott Pilgrim, and I had done some visual effects supervising [on the] production side with Gore Verbinski on A Cure for Wellness, so when Edgar’s collaborators came back to DNeg to talk about Last Night in Soho, I was kind of up at the bat.

BTL: Were you working at DNeg in London or were you in New Zealand, and then moved there?

Proctor: I started out in the Bay Area, then moved to New Zealand for a couple of years and worked on Lord of the Rings, and then I moved back to the Bay Area to work on the Matrix sequels and sort of kicked around the Bay Area working on various projects for a while. And then we moved to Australia, and worked at Rising Sun, did some visual effects supervision there, and then just 11 or 12 years ago, I moved here to London.

BTL: You mentioned starting in compositing, so at what point did you move up to VFX Supe? Were you a “generalist,” a term I’ve heard a lot from other supes?

Proctor: I think that my background as compositor has really helped, having a finishing eye of things, and an eye for composition, and being able to envision the bigger picture, and relentlessly pursue image perfection. I think those are the sorts of strengths that I brought to it. Also, I think what I learned on the first Matrix was there are a lot of really precise small steps, atomic parts of the process, and if you got these things right, that you knew you could rely on later on down the line, you could scale, and you could rely on your foundation. I think what I brought to visual effects supervision is this sort of meticulous craft, just from learning you have to get things right, but then you can count on them.

BTL: I know Edgar’s older brother, Oscar, has always been involved with the visuals and drawing stuff in the design phase. When you got the script from Krissy and Edgar, did it include some of Oscar’s drawings for some of those scenes?

Proctor: I got the script first, read that. I had a meeting with Edgar and talked about it in the very next meeting, probably the next week. In the first meeting, Edgar gave me a list of 16 movies that were essential viewing, so I had a lot of homework to do on that, and then the next meeting, Oscar was present, as well as [Production Designer] Marcus [Rowland]. We really got into the visuals straight away, and Oscar’s concept art. He did lots of sketches and brought a lot to it. He’d obviously been working with Edgar and thinking about it for quite some time. He’s got an illustrative style which we needed to expand upon with photographic tests.

I did a few very, very rudimentary lo-fi tests at DNeg in one of our little studios and got some of the crew at DNeg to play Shadowmen, playing with the techniques we might use to obscure the facial features and different looks for that. Following that, we were having meetings at the same time about other effects in the film, as well: how we were going to achieve the fire, the silhouettes, the hands against the walls, and lots of the mirror gags. We were exploring all sorts of films in which mirror gags had been employed. [I] wanted to find ways that we could innovate and do things that were neither fully digital, but they weren’t going to be completely practical either, o really keep the audience guessing, trying to maybe pay homage to other films, but create our own mirror gags that are even better, to one-up them. We got into doing photographic tests at Ealing Studios fairly quickly, brought in some actors to play Shadowmen, and we began playing with the makeup and prosthetic effects that would be used to hide their faces while we’re on set.

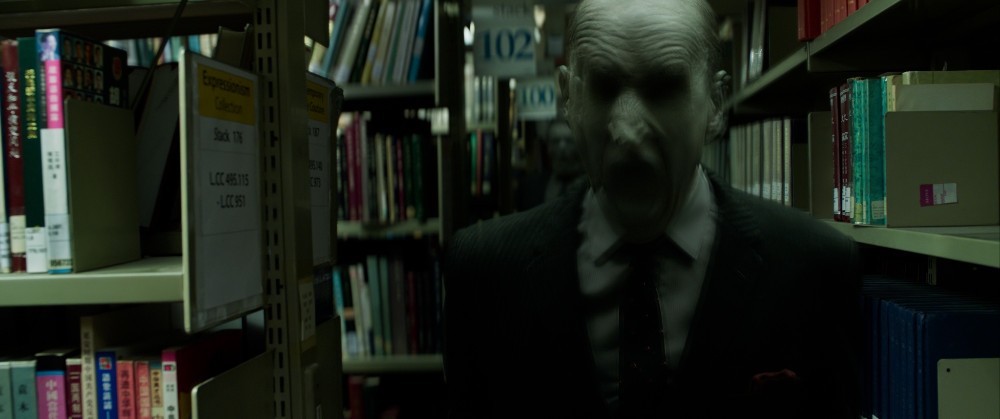

Edgar was really keen at the outset that the film needed to have this kind of tactile quality to it, like the British films from the 1960s that we were all using as our points of reference. He wanted to make sure … we never wanted it to look digital. It was important to him that even on set, although there was going to be an effect applied, that the actors and the crew even, would all have a sense of what the Shadowmen were. We knew from the beginning that there was going to be some kind of prosthetic element to it, even if there was going to be a digital enhancement or takeover or wholesale replacement of it. We got Barrie Gower, who’s an amazing prosthetics makeup designer, to create the sculpts of the face. There’s a pretty painstaking application process that needed to take place at the beginning of each day. For their skin, we applied this sort of charcoal-colored, gray makeup to their faces to make them more shadowy and mysterious-looking. And then in visual effects, we need to make the eyes sunken, so there’s a subtractive element of the digital effects that was done there, putting this membrane over the mouth.

One of the drawbacks of using the prosthetics was that they couldn’t see or breathe very well, so eventually, we moved away a little bit from using the prosthetics, later on in the shoot, once we were all in the swing of it, and we knew what they were meant to look like. And once everyone had the Shadowmen in their head, we began to move away from using the prosthetic a little bit. It did slow the day down somewhat. As great as it looked, the actors had a hard time performing in some of the more physically-exhausting shots where they were running. In the library, for example, they couldn’t see well enough to avoid running into bookcases. It was a bit of precision work running, which was going to be difficult. So we did end up getting away from using the prosthetics, and we did fully digital faces on. We could also add more expression to their brows or their mouths if we were doing it digitally. The makeup, as great as it was, as good as it looked, it had a tendency to kind of restrict the facial expressiveness.

BTL: I know the production was shut down due to the COVID shutdown, splitting the production in half. Was a lot of the Shadowmen stuff done early, since you knew had to do VFX for much of that?

Proctor: We had firmly established what the Shadowmen were going to be. There were some cases where we had shot on locations, and due to time constraints, we felt like maybe we’d not done the best version of the shot we could have if we had a bit more time. In the library, for instance, I think we all felt that we could make it scarier and punchier, and there’s a scene in the alleyway where we were just running out of darkness, the sun was coming up, so we didn’t get to shoot the alley being surrounded by the Shadowmen in the alley with as much gust as we wanted. There was a version of the film that existed up until we got to do the reshoots where it didn’t have that.

We got to go back and reshoot that during lockdown. We were one of the first films out of the gate and shooting at Pinewood, and it was great. The first time around, we were doing it on the streets of Soho, which is a total circus, and it never stops. It’s always going on. In fact, at three in the morning, it’s probably one of the craziest times to try and get around and operate a film unit. I was really happy that we got to do some of that stuff on the backlot at Pinewood instead. It looks fantastic, and you can’t tell that it’s cut in at a soundstage. It looks absolutely perfect. Marcus’s team did such an amazing job recreating. At that time, our DOP [Chung-hoon] Chung, who was part of the main shot, obviously, wasn’t able to come back for the additional photography, so our Second Unit DP Oliver [Curtis] came back and just knocked it out of the park. It looked so good.

BTL: Let’s talk about the Café de Paris sequence. It’s such an amazing piece of work, switching between Anya and Thomasin with all the mirror stuff, as you mentioned before. Was a lot of the early previs done to figure out how to make that work?

Proctor: The film is [story] boarded to the nines. We’ve got very good boards for any of the technical sequences. The first sequence was the first dream where Ellie pulls the blanket over, and we travel down this magical realist blanket tunnel, and then, she ends up wandering out of this tunnel or alleyway in Mayfair. We had boards for that. We had a pretty good idea of how we wanted to execute that, how we wanted the different elements to be shot and how to stitch it all together. The mirror shot in the foyer, when she goes into the Café de Paris was going to be a little bit more complex, and we needed to previs it to work out exactly how to break it down and approach the different parts of it.

That’s such a great example of how the different departments collaborated well. Visual Effects working with, first and foremost, the actors and great performances, and Jen White, our choreographer, helping them work out their timing, so they can perform the same part in absolute lockstep with one another. Obviously, Anya and Thomasin did a brilliant job, but also the Phelps Twins, Oliver and James Phelps, who play the cloakroom attendant, come and take their garments from them. It’s a special effects gag where the mirror in the foyer slides back to reveal a second set, which is there. So there’s a mirrored set, and at the tail end of the shot… let’s see. What’s the best way to explain this?

When Thomasin first walks in, we see her reflection in the mirror, and then, as the cloakroom attendant walks past the mirror, behind his body, the edge of the mirror is sliding past to reveal Anya Taylor-Joy standing on the other side on a doubled set. When we push in, we exclude Thomasin from frame, and we push in on Sandie, we’re using a second take that was stitched-in seamlessly by visual effects. A great part of the credit is due to our an absolutely incredible Steadicam operator, Chris Payne, who did this sort of thing flawlessly throughout the film, almost like a human motion control unit, being able to repeat his moves that made it a joy to composite it all together. It meant that visual effects was able to just make it completely seamless. We added a lot of grace notes to it, too, like a fingerprint on the mirror, when she taps it. There’s a digital bevel on the mirror and a sense of some faint dust marks and surface on it. There was a little bit of cleanup work to do here and there, making sure all the stitches in the plates, the different elements, kind of work together seamlessly.

That extends through to the dance, as well. That’s another example, like the mirror shots, where we wanted to combine practical and digital effects. I think there are five different switcheroos in the dance scene between Sandie and Ellie, and the first one is fully digital, where we shot a second pass — again, Chris doing an amazing job on the Steadicam — and the dancers all repeating their moves precisely, so that they’re in the same place and frame at the same moment in each take. We did a digital wipe, and then the other four switches in the dance were done in-camera, but there were ever-so-slight nudges given to them digitally to help move them out of frame, nice and elegantly or scoot someone off to the side at just the right moment.

BTL: Edgar mentioned there was a lot less editing than most people thought. I think most people who see that sequence thinks it’s cut, cut, cut, cut, cut… but in fact, there was a lot of stuff done practically, as you mentioned. I remember when watching the extras on Shaun that Edgar was already using CG blood and gore back then to accent what was done on set. Did you do some of that in Soho as well?

Proctor: There was a fair amount of stage blood thrown around on this film, for sure, but it’s a lot of work to clean it up and reset. There were a few places where we added more blood, just to help the day, and to make sure that the actors didn’t have to be clean. We didn’t have to have changes of costume, we could do the blood digitally.

BTL: Without giving away the big twist, I’d like to touch upon the grand finale, though I hope by now, people reading this will already have seen the movie. The climax includes this amazing glass staircase, and it involves so much switching between reality and fantasy. Can you talk about how you prepped for that?

Proctor: That’s an example of Oscar’s concept art being a really fantastic guide from the outset. I think that was in one of the first batches of concept art that we were delivered. It’s just a fantastic image, and it harkens back to the curved mirrored staircase in the Café de Paris itself. The finished image looks just so much like the art, I think we really nailed it. In order to shoot it, Marcus’ art department built this incredible black Plexiglas, I suppose, or acrylic staircase on one of the stages at Ealing. There wasn’t a lot of room, so we had black drapes around it to give it this empty space. SFX pumped a lot of smoke in, we kind of simulated the look of fiery lighting, but the staircase itself was actually really quite lethal. There were like super-sharp edges on it. We had to add padding to it, to keep it safe. There were quite a lot of safety mats to paint out, and then, we needed of course to make it all crack. By the end, I think we almost completely replaced the set-piece with a digital version of it, which is beginning to crack and shift as Sandie’s heels dig into it, as she walks up, and then adding lots of digital embers and a sort of swirling, slightly psychedelic effect to it.

BTL: With the COVID shutdown, were you able to work on the VFX in between the two shoots?

Proctor: Totally. There was a huge amount of work to do. The other thing I want to mention – because I think it’s one of the highlights of the visual effects in the film – is the 1960s period enhancement of the location-based plates around Soho, making it look like the 1960s. There was great set dressing, but it was usually quite local to where we were shooting, and we needed to extend buildings, add crowds, and period-appropriate vehicles off into the distance.

The biggest example of that was Piccadilly Circus. We worked on that pretty feverishly throughout lockdown, and before we could recommence our additional photography. Piccadilly Circus is a fully CG environment. We shot plates of the car, again, wanting to keep the camera moves physically-based and not too “flying magic camera.” We previs-ed that, and we shot it on an airfield, the Triumph Spitfire, Jack’s car, driving through, with a cherrypicker standing in for the fountain in the middle of Piccadilly Circus. We replaced the airstrip background entirely with this huge neon-drenched world, and we did a lot of really meticulous picture research, finding all the brands for that particular year in 1965, making sure that everything was in the right place, and then, of course, getting it all cleared. I’m really proud of it. I think that that little beat in the sequence just sits in with the rest of the film, and gives it a tactile, practical feel to it.

The other thing that was kind of a revelation was, during the lockdown, I was able to begin working with our in-house team, like a small team of freelancer artists. So, the vast majority of the shots was evenly split between DNeg, and our in-house team, and our in-house team are these artists who are all working remotely. We just got into the swing of it really quickly and easily. It was a nice way to see people, while we were all in lockdown. It was kind of a lifeline in some ways, and it was a beautiful team to work with.

Last Night in Soho is available digitally via VOD, and it will also be available on DVD and Bluray on Tuesday, Jan. 18, 2022. You can also read our previous interviews with Wright and co-writer Kristy Wilson-Cairns and Production Designer Marcus Rowland.

You can also watch a VFX breakdown from DNEG and an extended reel of some of the VFX work discussed in the interview with Proctor below:

DON'T LOOK NOW if you haven't seen #LastNightInSoho yet, but as an end of 2021 treat & taster of making of content to come, let me highlight the amazing VFX work by Tom Proctor & the wizards at @DNEG. As you can see, it's a devious mix of in-camera magic & digital sorcery. Enjoy. pic.twitter.com/jwB0tqrEWo

— edgarwright (@edgarwright) December 31, 2021

All photos courtesy of Focus Features.