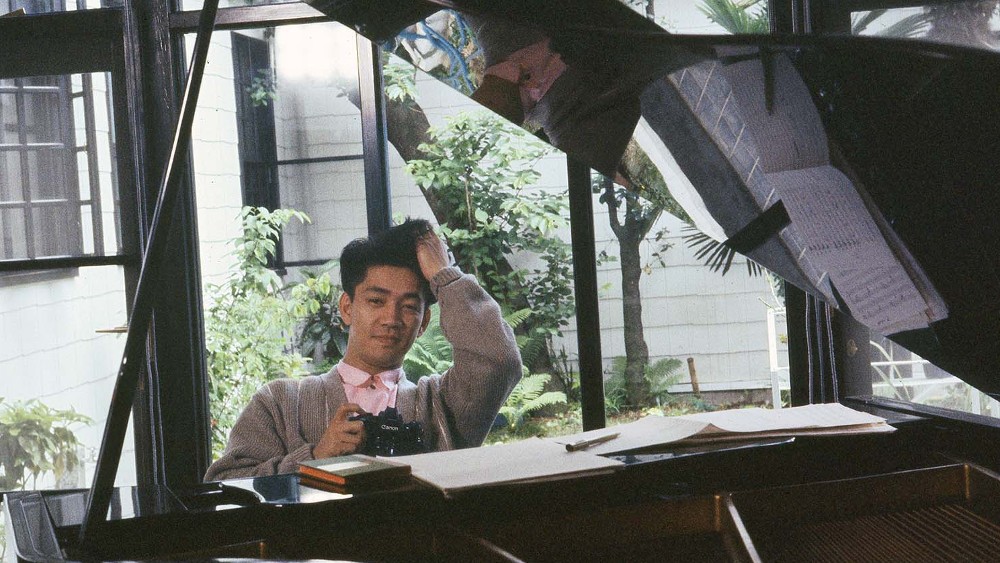

In 1984, director Elizabeth Lennard travelled to Tokyo, Japan, to make a documentary about musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, a 62-minute film that captured him when he was just being discovered in the States outside his electronic group, Yellow Magic Orchestra. The resulting film would be called Tokyo Melody: A Film about Ryuichi Sakamoto.

At that time, Sakamoto had already starred in and scored Nagisa Ōshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (starring David Bowie), but it was before he would co-write the score for 1988’s The Last Emperor with David Byrne and Cong Su, for which they would win the Oscar. Before his death earlier this year, Sakamoto would go on to become a renowned solo recording artist and composer, most recently scoring Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s The Revenant with Alva Noto.

Lennard’s Tokyo Melody has been revived for a special sold-out screening as part of “Japan Cuts” at New York’s Japan Society this weekend, and Below the Line had a chance to speak with Lennard recently about her film, which oddly, is even more fascinating forty years after when it was made.

Below the Line: I really loved how your movie is a time capsule, not only of Sakamoto during that period, but also of Tokyo and Japan in general. How did this get going? How did you meet him and start to make it?

Elizabeth Lennard: Yellow Magic Orchestra had done a US tour in the 70s, and their records had been distributed by A&M. I had done record covers for A&M when I was very young, coming out of college at UCLA. I do hand-painted photographs, so I knew the people from A&M Music, but I’m based mostly in Paris. Flash forward to the ’80s, and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence was shown at the Cannes Film Festival. I was privileged enough to see it there, and that’s when I discovered Ryuichi’s music, and I was bowled over by his presence [in the movie] and the music.

At the screening, there was also a producer I knew from French national television – I.N.A. [Institut National de l’Audiovisuel], experimental TV. It was not a TV channel, but the French Film Archives had a production [arm], so they were able to produce some films. Muriel Rosé, we were like, “Wow, who is this? Ryuichi Sakamoto, this music is incredible.” I had already made a couple of short films, one about two musicians. They said, “If you have any way of finding Ryuichi Sakamoto, maybe we could find some budget to do the film.” This doesn’t happen to you as a filmmaker often, so it didn’t [fall on] a deaf ear, as they say, but I had no way of getting in touch with [him]. I happened to be going to New York, and I happened to go to Odeon, the restaurant, which is still in New York.

I was there, and at the next table, there was a person who I had worked for at A&M Records, a man named Jeff Ayeroff, who went on to head Virgin Records. I remembered that YMO had been distributed by A&M, and he said, “You’re lucky because at this table, there’s somebody who worked with them on their tour, Kiki Miyake,” so she put me in touch with Ryuichi Sakamoto, who was going to Berlin to record a record with David Sylvian, Forbidden Colours. They had done the music for Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, but I don’t think the record of David Sylvian had been released. I’m not sure of the chronology, but anyway, he was in Berlin, and I went there and I met him. I showed him some of my hand-painted photographs of New York, and he liked them and said, “Okay, come to Tokyo, and meet with me again, and this can work.” So that’s how it happened.

BTL: Did he have any concerns or with any limitations in making this movie when you first met him?

Lennard: He was a huge star in Japan already. [YMO] was called the Beatles of Japan, but not in the Western world. I would say, in hindsight, it was a feather in his cap to say “yes” to me, because I was a young American, having hardly made any films, and we really only had four shooting days with him. That was the agreement, so that every time you see Ryuichi Sakamoto, it’s four shooting days, and the other shots he wasn’t with me.

When you see the recording studio, it’s a place called Onkio Haus, and from what I understood, it was the biggest and best recording studio in Tokyo besides the NHK TV, a very big, very well-equipped recording studio. In the ’80s, there were some studios that were better than others, so it was a major recording studio, which Ryucichi Sakamoto had to rent. As you know, it’s very expensive to rent those recording studios – it’s a huge amount of money. That was part of the agreement, that he would take care of the recording studio.

BTL: Tokyo Melody was an interesting counterpoint to the more recent doc about him, called Coda. In recent years, he had his own studio, but it’s amazing to watch him in 1984 playing this Fairlight, which was this hugely expensive computer workstation that cost as much as a small car, it didn’t even dawn on me that it was at a studio.

Lennard: The Fairlight was his new toy at the time, and as you say, $20,000 — somebody said he looked it up and it was $30,000. What you could do with the Fairlight, you can probably do in your home computer without a problem, even on your phone now. But we shot this in ’84, so it was the beginning of being able to use floppy discs and computerized things.

BTL: Was this originally going to be shown on television since the movie is just an hour long?

Lennard: It was shown on French national television, but at the time, they were quite flexible about the time, because really, you’re supposed to do 52 minutes, but this was 62, so it was okay.

BTL: Your film also has footage of Yellow Magic Orchestra, so did you have any time to talk to them about Ryuichi, or talk to his wife, Akiko Yano, to whom he was married at the time?

Lennard: The footage of Yellow Magic Orchestra is from a concert film. Obviously, when you see them at home, it’s their home, and you see them playing piano together, with Akiko. Yellow Magic Orchestra had already broken up, it was over; that was concert footage. I know they used a little bit of my footage in Coda. If you see footage of Ryuichi [when he was] young, it’s from my film.

BTL: So you go to Japan, get all these interviews and footage of Ryuichi, and then you go back to France to edit it?

Lennard: I was actually allowed to go there to for location scouting. They sent me to Japan by myself, not speaking Japanese on my own, doing location scouting, and also to meet with Ryuichi again, and to make sure everything was okay. So that worked out, and it was a short visit, and then I came back to France, where I wrote a little synopsis of what I was planning to do and so forth. Then I came back to Japan for seven days shooting, and I stayed a little bit longer to do my photographs, and then I came back to France, and we edited it.

I was very lucky, because I had a Japanese editor in France, Makiko Suzuki, and she was unique, because she was Japanese, but she was a film editor and she spoke perfect French. Because the film really is in Japanese, but Makiko really understood the film. It’s very important to have a good editor, especially on this kind of film, and especially if it’s in Japanese, and you don’t speak Japanese.

BTL: I assume he spoke some English at the time, so did you ask him questions in English and he responded in Japanese, or did you use a translator?

Lennard: If you remember Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, he does speak a little bit of English, but he told me that he had learned that pretty much phonetically for the film. He didn’t really speak English that well. Later on, he spoke English. In fact, when I was making the film, he said his English was not so good. He wasn’t secure with his English, so I asked him a few questions.

There’s a little interview with the Fairlight; that’s done by a Japanese-American who was with me, and she asked those questions in Japanese, and you hear her voice. Otherwise, I was able to ask him some questions, and then he might answer in Japanese. He could understand, of course, but then he wanted to answer in Japanese. But there’s very little talking. When he speaks to me, which is very rarely, he might have been answering in Japanese, even though I might have asked the question in English.

BTL: Did Makiko translate and transcribe all the interviews for you, so you’d know what to include in the movie while editing?

Lennard: She didn’t transcribe, but there was somebody named Ryoji Nakamura, and he was a very professional French to Japanese, Japanese to French translator. He lived in France, and he worked with high-end French publishers and published famous Japanese writers into French. I do remember that he transcribed everything, and he did a translation for me. But again, there’s not very much talking – it’s mostly music.

BTL: Other than the bit that’s in Coda that you mentioned, has this ever been shown in the States before in some form or other?

Lennard: What happened was it was shown in film festivals all over the world when it came out. In the United States, yes, it was shown at Filmex [in Los Angeles]. It was shown at a few film festivals, but it wasn’t distributed yet. Now we’re trying to get it distributed, so it hasn’t been shown in the US. I think it was shown at Filmex, and maybe a couple of other film festivals in the United States. It was shown in New York at New Directors, New Films.

There was somebody called Richard Roud – he was the head of the New York Film Festival, and he also did New Directors, New Films, and he invited [Tokyo Melody to play there.] The films he chose were really good. It was the first time a Pedro Almodovar film was shown in the United States, I remember that, but because it’s only an hour, he showed it with a film called Small Happiness.

BTL: His wife Akiko is still alive, so was she involved with getting Japan Cuts to play Tokyo Melody, or how did it end up there?

Lennard: First of all, it’s his ex-wife Akiko; he had another wife. But no, “Japan Cuts,” they found me. This is the world of internet, and I do have a website, and you can reach me via the website. I do get requests via that email, so I think that might have been how they found me. This was several months ago, so the Japan Cuts film programmer, he told me he used to be a projectionist in another life. I said, “Okay, I have a copy of the film in my basement with English subtitles, but nobody had seen it in years.” He set me up with somebody in Paris who checked the print to see if it was screenable. We checked it – I hope it won’t break, but he thinks it’s okay – and he sent it to New York.

BTL: This was a 35mm print?

Lennard: 16.

BTL: They didn’t just want to digitize it right away, and they’re going to show your original 16mm print?

Lennard: There’s a certain crowd that wants to see 16mm and isn’t afraid of it breaking. It hasn’t been reissued and redigitized yet. We’re working on all of the reorganizing, because the contract expired. We’re working on getting it redigitized. We hopefully will make a DCP and be able to distribute it in high-res, as they say. We haven’t decided if it’s going to be 2K or 4K.

BTL: Since it’s been forty years since you made the movie, do you watch it now and want to make changes if the opportunity arises?

Lennard: As a director, I definitely don’t want to make changes. I’ve been making films for a long time, and when you just finish [a film], you see things when you’re doing the subtitles, there are moments before it gets released, where you think, “Oh, God, I should do this or that.”

There’s still time to do some changes, more in terms of text or whatever. It’s true in today’s world, making the changes it’s somewhat easier than before, but still, it involves a certain cost, as you can imagine. But no, there are no changes that I would like to make.

BTL: What would you like people to get out of seeing your movie now? I’m not sure how many people saw Coda, but I imagine that younger people might even be aware of how famous he was back in the ’80s when you shot this.

Lennard: I think you said in the beginning that it’s like a time capsule, and I think that’s quite apt. When you make a film or do a portrait of somebody, it’s always like a time capsule of the way they are in that moment. They’re always that way in my imagination. I photographed the Black Panther Huey Newton, in 1972. I was very young, but for me, he still looks in my photograph. Hopefully, people who see the film and who maybe don’t know Ryuichi will discover him the way he was then. That’s the way he is in the film. It’s an interesting thing about that about time. Time is stopped in some way in old movies, and I like that.

Tokyo Melody: A Film About Ryuichi Sakamoto is playing as part of Japan Cuts at the Japan Society in New York City on Saturday, July 29. The screening is currently sold out, but hopefully, it will get some sort of U.S. distribution soon.