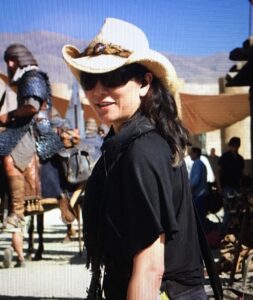

When Filmmaker Niki Caro (Whale Rider) took on her most ambitious project, attempting to bring Disney’s beloved animated film Mulan into a live action setting, she called upon one of her longest collaborators, Hair, Make-Up and Prosthetic Designer Denise Kum, who had worked with Caro going back to their student film days.

Mulan stars newcomer Yifei Liu as the title character, an adventurous teen girl from a poor Chinese village who steps up to take her father’s place in the Emperor’s army, disguising herself as a boy to train in a camp full of inexperienced soldiers being molded into shape by Donnie Yen’s Commander Tung. Mulan cannot let the Commander or any of her colleagues know her secret. At the same time, the witch Xianniang (Gong Li) has teamed with the treacherous Böri Khan (Jason Scott Lee) to amass an army that can defeat the Emperor (Jet Li) and his roughshod army.

Below the Line got to speak with Ms. Kum on her only day off, since she’s so hugely busy, especially with all the COVID protocols currently in place. This is a fairly long and detailed conversation about her work on Mulan — for which she received three nominations from the Make-up Artists & Hair Stylists Guild. She had many incredible thoughts and insights to share about her work on the film, but we enter the conversation midway through as we transitioned from talking about COVID to talking about Mulan.

Denise Kum: I think we’re living a very strange heightened time at the moment, and all of us are hoping things would get better, but it’s just hard to know, isn’t it?

Below the Line: Here in New York, they’re getting the vaccine out there super-fast. I think I saw that New York City is almost 20% fully vaccinated. From your accent, I’m guessing you’re originally from New Zealand?

Kum: Yes, I was born in New Zealand, and I’ve lived in London, God, 22-23 years now. I go back as often as I can, but at the moment, I can’t get in because they’re not letting people in. [laughs]

BTL: Even though you’re from there…

Kum: You have to book in advance, and there’s only so many hotels you can quarantine yourself in, but I can’t even get time off work to go there. Because you have to go there, quarantine for two weeks, and then come back and quarantine for two weeks. That’s a month of quarantining before you get to do anything in between. I don’t have a month just to quarantine. We’ll have to wait on that one.

But yeah, I was born in New Zealand. So it was very lucky that Mulan was actually going to be shot in New Zealand, which, of course, when Niki had been approached to do the film, she never knew if they would definitely do it there. I think they were talking more in China or maybe even Canada, so it was kind of good fortune all around, really, that those of us that are from there, got to go back there as well.

BTL: Having worked with Niki Caro going all the way back to Whale Rider, what was your background before you got into designing make-up and then hair?

Kum: Niki and I went to art school together. I was studying sculpture and film, and she was studying film and had also done sculpture. We met through there, because we used to make student films, and then soon after we made music videos and then dramas. Whale Rider was one of the films that we’d done, but before that, we’d done some independent films and short films and student projects. I kind of got into make-up completely by accident, because I was always approached by… we had to crew our own projects, so I did everything from art department, make-up and costume in our little low-budget lo-fi way, way back when. My skills are definitely in making things and in painting. I was definitely not going to be doing the lighting. That’s kind of how the love and the interest of it sparked, but really more from a conceptual element of, “We’re making a project, what do we need to create? What do we need to do? Hey, this would look great!” That’s kind of how it all really happened.

And then I just kind of read everything, and because I had a major in sculpture, make-up artists would often ask me how to make certain things or make molds — or what is now called prosthetics – because we made everything ourselves. That’s kind of how it started, then I got asked to do projects while I was working as a full-time artist. I would work as an artist, plus the multitude of part time jobs you have when you’re putting yourself through a double degree. Plus, I started taking on make-up work, and started doing courses to learn more, but pretty much took out loads and loads of books — the very old Tom Savini books and all the old make-up books and started off making and practicing at home… and on funny student projects. That’s kind of the very beginning of it, because I come from a fine art background and would do make-up alongside, practicing as a fine artist.

BTL: I am really impressed that you do hair, make-up AND prosthetics, because usually that’s three different people or different teams.

Kum: And I still work with lots of people who are specialized in those things. Particularly with something with Niki, she wants to talk to one person, and also, it’s very different in New Zealand and in Europe. We do train to do more than just the one thing. I know it’s very unionized in America, but there are still people here, of course, in Britain, who will only do wigs or will only do hair or only do make-up. I guess because I come from a painting and sculpting background, I happen to be making cages for wigs or sculpting and making prosthetics. Mine, I guess came in more from a color and painterly background, but definitely as the projects get really huge, I will always say, “Oh, I think we should get a prosthetics person just to take care of that,” particularly if you’re looking after lead cast. It just depends on how huge it gets. But I do find it quite natural to design a 360-degree being rather than stopping at the hair or stopping where the prosthetics join the face. It just feels more natural to me to be able to consider the whole componentry.

BTL: That makes sense and Mulan must have given you a chance to really explore all aspects of your craft, including some of the make-up where you’re literally painting on Yifei Liu, the actress playing Mulan. When did Niki come to you with this? It was obviously going to be very different than The Zookeepers’ Wife, which would be more straight-forward.

Kum: Well, she had mentioned that she had been asked to do it. I don’t know if you remember, but it was postponed a few times, because they still hadn’t found the wonderful Yifei [Liu, the film’s star]. We had kind of started soft prep, and then we had to postpone it, because they hadn’t cast Mulan, and then I think it got pushed slightly again. For her, it was a very long process, because the casting was integral. Obviously, they had a lot of location scouting to do. The Art Department had started prior, and a lot of the research had started. When you get asked to do a film, when you start researching, you kind of become obsessed about it and you start delving in, so it was a very good trick for them to hook all the HODs in, to become obsessed about that particular time, because you just start collecting everything together.

The more time you have to imagine the world, the better the design ends up rather than everything being last minute and rushed. I can’t really remember the exact year, but it’s been a few years back now. We had started talking about it, and then it became a reality, and then of course, Disney got in touch, and you have to be interviewed and send your CV in, and then I was asked to do it. It got pushed a couple of times, and then when they found Yifei, we just kind of went into overdrive to start getting everything together.

I was very keen to try and use a lot of people from Australia and New Zealand in the team, because having come from there and having worked from there rather than taking everyone from abroad. It was a real community spirit in terms of putting the project together. We also had a team in China, and we had a team in L.A., so I was very lucky to work with a really good mix of skills and a mix of people, and my L.A. team was incredible. I was very blessed to have them, because we did a lot of additional photography, actually only just before it came out, so December 2019.

BTL: They make historical epics like this in China all the time, and I’ve seen many of the ones with Gong Li, Jet Li, and Donnie Yen, so had any of your make-up people from China worked on those other movies?

Kum: Gong Li brought her personal make-up artist who’s also a good friend of hers, and even though she’s a beauty make-up artist, she became part of our team. I did all of Gong Li’s hair and make-up, but she came along and helped do the stand-by and was just there to look after her really, because Gong Li’s costume and all her talons, very uncomfortable. You’re basically getting her rigged, and then she can’t eat or go to the toilet or do anything except to do her thing, because we’d have to take all her talons off, so she could eat or go to the bathroom. That’s a labor of love. She was a big rig, and we took a long time to process her. And then often, she’s on the stunt wires, and God knows what else. Also, in China, we had a very big team, because when we shot there, we used people from all around the region that had to come in, often from Hong Kong. The thing is that this was a particular type of film, because it alluded to so much historically, and creatively within the Chinese realm, but it really is a fresh take on things. We really wanted to do something that was honoring the animation and imbued with Chinese culture, but very much its own kind of hybrid. You couldn’t say it’s a purely Chinese formula or it’s a purely Disney film. I think it’s very different than a lot of Disney Princess films, and the make-up and hair along with the costume and the art direction and the production design, we worked to get very homogenized, because we wanted to make a palette that was almost like honoring that over-bright over-colored world of animation. Because, you know in China, it probably wouldn’t have been that bright at that particular period.

It’s almost like making it really fun and making it very luster-full and very colorful, so it really bought out the humor in the film as well. I think Niki did a really special thing, because the battle scenes are very epic. They’re very elegant, though. They’re not just blokes fighting. Mulan herself comes across more as a warrior than as a princess. And I think there’s a wonderful characterization, so all of the actors like from Böri Khan to Xianniang to Jet Li as the Emperor. All the different characters, there’s a weight to the way that they look, and the way that they sit in the film. Essentially, we follow Mulan’s journey, so even though it is very different than the animation, I think it fleshes out the characterization, and it makes a deeper story, I think, which is honoring the original fable of The Ballad of Mulan. That really influenced me in terms of the make-up, to do things really colorful and to make it really fun. Also, because I have two young daughters, it’s probably the only film that I’ve done, that’s probably okay for them to watch. No blood and guts and no emotional turbulence like the type of films I normally work on.

You’ve probably seen a lot of the scenes like the matchmaker scene and getting ready. I really wanted everything to be quite visceral, and Niki and Mandy [Walker], our DP, were really into that, so on a pre-shoot, we did like a storyboard about how the make-up would be applied in stages. I based it very much on layers that you would apply, and we ground up pigments and used contemporary make-up, but to be like pastes and things made out of flowers and ground up pigments. That was the whole idea of the layering of that to create almost like this mask-like face and having fun with it. There’s a great line when she’s talking to her sister: “This is my happy face, and this is my sad face,” and basically, she looks the same, because she can’t move her face – the joke of wearing too much make-up. We really could have fun with that scene and the over-the-top hair. When they’re inside the matchmaker’s house to show almost ritual, to show this whole kind of thing in Chinese culture of keeping face and presenting oneself to honor the family. I really wanted to go over the top with that look, because then it really helped heighten the incredible naturalism and the dirt and the grit of the battle scenes. All of her squad, all of the boys that are training to be in the Emperor’s army, they all have tiny little details, because we wanted them almost to be cartoon characters, too. I really use the idea that a lot of Chinese boys can’t grow facial hair very well with these tiny little patches of hair or eyebrows were a certain shape or quizzical balance. I would make some of the boys look more feminine, so that she would sit in well with them.

So little details like that, when you line them up, they’re like the Seven Dwarves — everyone has their own little quirks. From a design point of view, it was really lovely to be able to take those kinds of quirks — the romantic one, or the tough guy, or the buffoon. So little things to give them a little bit of onscreen presence around her as a central character, because she has to go from a village girl, teenager, to this over the top ritualistic make-up, and then into being disguised as a boy and then dirty and then reveal her as the warrior woman with this fantastic hair that was doing its own stunts.

I wanted everything to be kind of seamless, but it’s a really fine line. It’s not just the way that it looks, but we were shooting in extreme heat and 40 degrees in China and in minus zero in the South Island of New Zealand. We were shooting in rain and sun and shine and snow. The hair and make-up had to go through a lot, and things would change. Hair, you’d have to make all the pieces that sit in and practically everybody was wearing a wig, because nobody has long hair that can always be in a top-knot. Everyone had wigs or facial hair or hair augmentation, so it was a lot of work just to get everybody out into the battlefield every day.

BTL: You touched upon a little bit of everything I was going to ask you about, so I’m going to go back and ask a couple of follow-up questions about some of them. As you mentioned in the matchmaker scene, you use the type of classic historic painted faces we might have seen in those times. Did you try to recreate some of the ingredients they used to make that painted make-up?

Kum: Well, of course, there’s no photos from there, so I used complete artistic license. What I did was I studied very much the literature of the time and all the scrolls, and I went to lots of museums – we have fantastic museums in London – and I looked online. The internet can be great at this kind of thing, because there’s also really fantastic collections of what they call funeral pottery, which was buried with as social standing, and there’s lots and lots of recreations of pottery. The pottery was all painted with a particular type of make-up, so obviously these make-ups are from people of a higher social standard. Make-up was always used symbolically then. The Chinese are very superstitious about what certain colors mean or what colors you should or shouldn’t wear, when you’re observing things. I grew up with this. Red is the color of happiness, or you wear certain colors when someone has died, so there’s all these lovely social rituals, and I really wanted to put that into the make-up.

But also just what the symbolism of colors mean. That’s why I wanted to reduce it to quite a heightened primary color palette, because also these colors to me, not only represent birth and death, but also red, yellow, white, blue, and black — they’re very, very retro early Disney colors. If you think about early Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. This is what I do – I try to flip things as a little kind of homage to early schlocky Disney characters. Very much, if you look at the matchmaker’s make-up herself, played by Pei-pei [Cheng], she’s the very over the top Grand Damme. So we had her with this crazy wig, which had two Mickey Mouse ears. Of course, these things are heightened, like in the middle of a village, you probably wouldn’t have someone as flamboyant as her, but we wanted it to be larger than life, and for her to be seen as this incredible matriarchal figure that everybody fears, because she’s in control of her destiny.

The white central panel of the make-up in the old days used to be done with lead and rice flour. So of course, we couldn’t use lead, but the way you see it being applied in that montage, we were really lucky to be able to do that, because it shows the additive nature of each color and what it means. A lot of people don’t understand that that panel, which I took from a lot of artists scrolls and these funerary pottery, they had the central panel, because it’s almost seen as a customary beautification. A lot of people get that confused with what the geisha make-up is, which is very different, and that’s an all-over white. This was almost like just a teaser. And then there’s little decorative elements of the makeup informed by Chinese stories. The Chinese have a lot of symbolism, so there’s lovely stories of when they push their face against a screen, if they’re listening, they get little marks. A lot of these stories came from myths and tales: A maiden who had a Plum Blossom that one of the Emperor’s concubines, fell on her head, and it stained her face, that became a popular thing that people copied. Now, of course, these are all fables and tales, so we don’t know what’s true and what isn’t. I took a lot of these little things to inform the flowers on the face or the crescent moon shapes that are painted. I wanted it to become very rudimentary and not too sophisticated, because of course, we have to believe they’ve done it themselves. They’re kind of like markings that have significance and symbolism. That’s kind of how those things came about, so it’s a lot from the fables but very much to do with practically what they could do in the village.

BTL: I do like how colorful the village is, because I’m used to seeing movies like Stephen Chow’s where he’d have a village that’s poverty-struct, but he’d make it very dirty and not much color and use it almost to comedic effect to show how poor they are, which isn’t the case here.

Kum: Also, we wanted to do something new. Even though you can look at all the Chinese films that you want, and you can look at all the Disney Princess films that you want, we’re doing something for a contemporary audience, and I think we all wanted to give it something fresh and and not just really copy a genre, so in that way, I think it’s probably quite different than a lot of other Disney films in terms of how it looks. But I think it’s also as much as it was Chinese, it’s also incredibly universal and also can satisfy many an eye, if you’d like.

BTL: I also want to talk about the soldier/warrior aspect of the movie where she’s undercover as a male soldier, and what was involved with that. Obviously, there’s a lot more dirt involved, but also, you’re working in arid climates with desert dust and trying to get make-up that looks appropriate but also stays on.

Kum: I always work with the team and that we do our time but once they’re on the floor, apart from last looks or final checks, really, on those epic battle scenes, you don’t want to be going in all the time and getting in the way – you can’t! Also in the close ups, there’s so much they have to do, so you kind of have to be like a ninja — get in and get out.

When I work on things of this nature, and I think this was what is good about coming from New Zealand. Before there was high definition, basically, the light in New Zealand is like high definition, so we grew up having that. You really see everything. Also, we have a very big hole in the ozone down that part of the way, so a lot of the make-up has to be mixed with sunblock or you have to have layers and layers of things that stay on with sunblock.

I think this is probably where my fine art background comes in handy, because my own work as a sculptor is all about layers and emulsions and different materials. So it’s a lot about experimenting with what’s going to work right. You can’t just buy the right product off the shelf, and then we’re working in different places – the dirt is different. The color of the direct light is different in China than it is in New Zealand. And we’re recreating the Crater Lake scene where it’s very yellow and sulfuric and bubbly, so we had travel dirt. We had Crater Lake dirt, we had battle dirt — different heightened levels that tell the story.

Also with her, because her character is not meant to wash because she doesn’t want to reveal she’s a girl, we use the dirt a lot to flatten the planes of her face and take out certain contours. You change the plane of the face to make it look either more masculine or feminine. You pull the color out to make it look more distressed, and then you pop it back in when she’s kind of revealing herself in all her glory. It’s really painterly decisions, and yes, you do have to test things. When the actors are sweating, you either have to leave that as part of it or you work out how to blend that in. When people are on horseback, you have to do what’s practical, you can’t keep going in. Those poor guys, the R0urans and the Shadow Warriors, a lot of them had full facial beards, they’re wearing black in the heating sun. The make-up artist ain’t your best friend when you’re having all that going on. [laughs]

Endurance was really something. When I look at other make-up on other films where it’s much on stage or more mannered or they’re at a lovely dinner party, I mean, you’re out in the wild west with something like this. You really are. Basically, it’s all about endurance and how that make-up not only looks in the final edit, but how you make your actors comfortable and how you keep that make-up and hair on, because there’s a lot of stunts.

BTL: I want to talk a little more about Gong Li, an amazing actress who I’ve interviewed before, but I would not have even known it was her if I didn’t look at the credits. What was involved with designing her look as the witch Xianniang?

Kum: Her design took quite a long process, because of course, with a lot of the actors who were coming from China – she was coming from France — we didn’t have a lot of pre-production time even. There was a lot of back and forth, and we’d send drawings and get feedback, but we really needed her there to do it in a staffed workshop. Bina Daigeler, our Costume Designer, obviously it started with the costume, because everything is so meticulous — it takes a long time. We had started with an illustrator and just throwing ideas around, and I got a model in there. I could do different ideas and put together a mood board. I put together a little book for her, so that I could give it to Niki and to Gong Li, so that when she came, we could discuss what she liked and what she didn’t like before we started doing templates and practicing on her. The ideas of a lot of her make-up came as a mix between kind of the conceptual ideas of her being a villain but also wearing a kind of a mask.

This is where the color white comes in, which is a very difficult color to work with in terms of involved make-up. Most people when they think of matte white, they think of clowns, or the Joker, or the white mask from Scream. It has a film rhetoric. It has particular connotations, doesn’t it? So to go back to Chinese history, kicking off with the whole theatrical masks, I loved how this was used as a base and things were painted on top. Even more than that, the idea of white represents, on the stage, an idea of someone who’s treacherous and cunning. It’s also the color of mourning and of sadness. I liked how that touched with the complexities of her character. She’s kind of a villain, but she’s also been wronged. She’s kind of a very #MeToo generation, but she also ends up being an ally as much as she is quite a complex character.

I kind of liked conceptually starting off that black canvas, if you like. Her eye shadow we wanted to be very strong and very Chinese, as if basically taken off the shape of a hawk’s feather. All the detail in her hair and how she has these braids that intertwine into the crown, I wanted to integrate the detail that Bina had in the costume. So she has a lot of amazing leather laced-up parts, so I wanted to bring that into the hair and into the crown, which is very bone colored.

It’s very collaborative the way that I designed her and also what she was made into. It’s kind of part runway meets fantasy in a way, and the talons came later, because also her other animal being the hawk, which she shapeshifts and morphs into, we also started looking at whether we would do contact lenses or whether we were going to have a VFX element? I think we all decided that would be even more encumbering and did we really need it? Because it’s pushing it into a very different universe than connecting her with human eyes.

The talons kind of alluded to that, and it was also because then they could become her stunt weapons, so there was a meaning and a reason for absolutely everything — nothing is just purely decorative in terms of her character and how she moves and what she does and the shape shifting. That was a lot of fun to do with her, but like I said, it was a long process for her make-up, hair and prosthetics. We had to find the longest hair we could in the world, because it’s really really long. We wanted to use real Asian hair, so that’s quite a heavy wig on top of the crown and the talons. This is all airbrushed, and I did all the eye make-up on top, so it’s a lot of layers.

BTL: I’m glad you mentioned working with costume, because I have to imagine the hair and make-up working with costume is crucial, as well.

Kum: Especially on something like this, because you have to know where your margins are. I am someone who does tend to work quite closely with costume, just because I think it’s really important to think of the the whole character 360, not just a floating head.

BTL: Have you been working on anything else this year so far?

Kum: I’m working on a project at the moment with Judd Apatow, and it’s a really funny project. And then I’m going back to finish the final two episodes of The Wheel of Time, which we started last year before we had to stop because of the pandemic. It’s filmed in Prague, and it’s based off the American author Robert Jordan, a high fantasy/sci fi, massive– it has a huge fan base, very much like Game of Thrones.

Mulan is now available to watch on Disney+. All photos courtesy Disney, except where noted. (Click on images for larger versions.)