Season 1 of Peacemaker, the John Cena-led spinoff series that grew out of James Gunn‘s The Suicide Squad, is now available on Blu-ray and DVD, so if you don’t subscribe to HBO Max, now’s your chance to catch up with the action-packed superhero show.

Cena’s title character puts together a new team of agents to infiltrate a covert group of aliens, referred to as “butterflies,” in hopes of saving the world once again. Cena’s trusty pet-cum-sidekick, Eagly — a bald eagle — is a scene-stealer, and he was fully created using visual effects, the work of the ever-present Wētā FX, which also created the enormous “caterpillar cow,” a space creature being used to provide the butterflies with their beneficial nectar, and the “Quantum Closet,” where Peacemaker’s father keeps his son’s vast array of weapons and special helmets.

A few months ago, Below the Line spoke to Wētā VFX Supervisors Guy Williams — a 21-year veteran of Weta going back to The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring — and Mark Gee, who has been at Weta nearly as long. Our conversation was especially relevant for those interested in the VFX aspect of filmmaking since we covered other things besides Peacemaker. We even had a chance to speak with Williams about virtual production, which turns out to be a passion of his. (You can also read our previous interview with the show’s overall VFX Supe Betsy Paterson.)

Below the Line: Both of you worked on The Suicide Squad, as well, so what was the transition like? Did Peacemaker come up while you were still finishing Suicide Squad? How did you find out that James was going to take that character off on his own path outside the group?

Guy Williams: There wasn’t very much overlap at all. James has finished working on Suicide Squad, and to us, it was just as out of the blue that he had written another whole TV show, all eight episodes, and then rushed it into production. It’s something he had close to his heart, and because we had a really fun time working on Suicide Squad, he approached us and said, ‘Hey, look, I’m doing this project. I’d love for you guys to have a chance to work on it.’

BTL: Besides Peacemaker himself, there’s not a lot of overlap, as far as what was required. What were some of the first things you had to plan or develop or research?

Williams: The irony of the situation is, I don’t think we actually did [anything] for Peacemaker on The Suicide Squad. The only thing that we could leverage was the silver helmet, and it was the only shared asset between the two films. Pretty much everything had to be figured out from scratch. We got a chance to read the scripts early on, and the first thing you do is, you start identifying the things that terrify you the most about the work that’s coming up. It’s not necessarily if it’s gonna be technically hard, but even if it’s just going to be esoterically or aesthetically hard.

Case in point, the caterpillar cow. We’ve done lots of large creatures, but something as unique and different as a caterpillar cow takes a bit of special effort. James was very, very clear about the fact that Eagly was very important to him. He kept on saying, ‘This guy’s like a star of the show. You have to get it right; every shot has to be 100 percent believable.’ We took that to heart, and one of the first things we did was kick off a big R&D effort. I mean, we’ve done birds before, all the way back to Lord of the Rings. We have a history of feathers, but feathers are one of those things that the industry still doesn’t do totally right. We set about figuring out the best way to do it, revising our tools, and just a lot of back and forth with a lot of very talented people here at Weta, led by Jason Galeon, trying to figure out the best way to solve this problem. That’s one of the first things we really put into high gear.

BTL: I’m a little confused about the time, because I think Suicide Squad was supposed to come out in 2020 and then it got delayed, right? When was it actually finished?

Williams: I think Suicide Squad was supposed to shoot over a certain period. James is one of those directors that’s a joy to watch on set. He’s the kind of guy that gets his days, and he sets himself incredibly hard days, too. It’s one of the reasons his movies are so interesting, [because] he choreographs all these beautiful scenes, which require a lot of setups, and then he sets himself about shooting only 12 set-ups a day, so they’re getting these amazing number of set-ups every day. I don’t know all the details, but I’m pretty sure he finished on schedule and that nothing caused the release to push, but I might be wrong on that, because the pandemic didn’t really hit until we finished shooting. When we flew out of Panama, [that] was a week before they shut down all the international flights, so we did have to post the film during the pandemic, but it didn’t impact the actual shooting.

BTL: Let’s get into some of Weta’s work on Peacemaker. Eagly, for instance, is a good example of a fully CG character. What’s representing Eagly on set? I know James has his brother Sean [Gunn] fill in for characters, but I’m assuming he didn’t do that one.

Williams: For the most part, they didn’t have a person on set playing the role, like he’s done in the past for Rocket [in Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy] or some of the other characters. They used a couple different stuffies, at times. For reference, they did bring out a similar but not the same eagle, very early in the shoot, just for a day, so everybody could see and understand it. For the actual shooting process, it was more of a traditional “protect space for Eagly.” If they had a shot where it was just Eagly, they would then frame up on a stuffie, shoot it, and then remove the stuffie and shoot a clean plate. For the most part, it was kind of old-school visual effects in that regard.

Gee: The stuffie was used, and it was quite valuable as far as what we’re doing, and lighting conditions, as far as the feathers reacting to the light. We originally started building based on the look of a stuffie, but then we found all this other reference. We went away from it for a little bit. It was a bit of a process that we started with. We tried it with the stuffie, and then we started getting into these other birds, and then, as you go along, you would find all this different reference, and you could see how differently these bald eagles work and look. Somehow, we ended up getting to a point where it almost looked like a bit of a seagull. It wasn’t until we started getting into the first episode and into the second scene of that, that we changed the design again. Eagly was evolving for probably one or two episodes, and then we had him locked down to his final look.

BTL: Eagly is so involved in the action sequences, of which there are many, particularly in the last couple of episodes. I’m not even sure how much of that can be done on set with all the actors and stuntpeople interacting with CG butterflies as well as Eagly. What is the production handing to Weta in terms of plates from the set?

Williams: James is no stranger to shooting this kind of stuff. He’s obviously done this a lot, so he understands how to protect for moments and how to protect for space. That’s an important concept. You don’t want to just shoot a plate with the actors and hope that you can cram the visual effects into it. He really gets the actors to understand, “At this moment, a 20-pound eagle slams into you, knocks you to the ground, and pulls your eye out.” The stunt people and the actors do such an amazing job of just leaning into it. The performances were there on the plate side, brilliantly, and all we had to do was try to back the motion of the bird into it. In that regard, it worked out really well.

As far as the butterflies go, [James] did a really good job of explaining how the butterflies go into people’s mouths. It’s not a peaceful moment. It doesn’t just zip in. It gets most of the way in, and then has to dig in through the back of the throat. Once he really goes into detail of the horror with it, the actors totally lean into that. They fill their mouth with blood, and as they’re trying to fight the invisible thing out of their mouth, they’re spitting blood out of their mouth at the same time. It made for some excellent integration points. In that regard, it was really good. Whenever somebody had to contact the bird, we used the stuffie or a “buck” they built. It was almost like an oversized bowling pin, [a] grey felt “buck” that John can hold onto and throw up to the skylights so that Eagly can fly away. For the most part, we had really good reference from the set.

BTL: James comes from a background of practical in-camera effects. Is he still able to do a lot of stuff on-set? I know you did some of the blood and gore, so is Weta enhancing what is happening on set to make it look better?

Gee: We kept a lot of the practical that he did shoot. We did augment a little bit on it, but most of the stuff that you see in there was shot in-camera. James is a magician as far as that [goes]. From his student years and his early films, he’s always done that, and I’ve learned some valuable lessons through The Suicide Squad, as far as blood and gore and going out and doing practical shoots myself to make sure we get it right. It was the same scenario in Peacemaker.

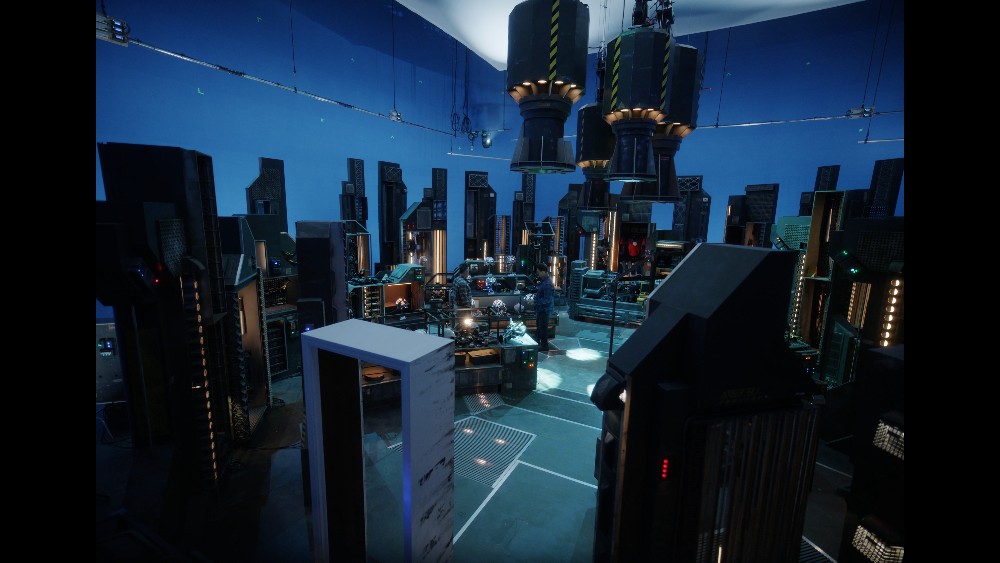

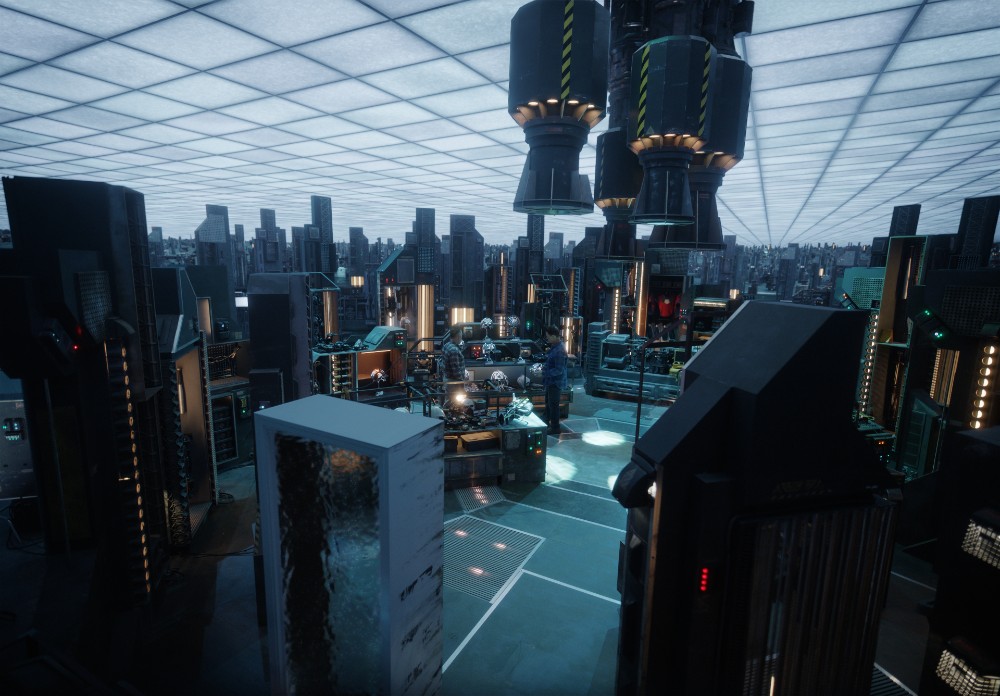

BTL: I also want to ask about the Quantum Closet, since that’s a really interesting space. In theory, they could build it and have set decorators do their stuff, but was it more practical to do it with visual FX, shooting on a green screen?

Williams: James’s desire was to have it larger than a set can be made. The original idea was that it was infinite, but it eventually got pared down to 200 meters across, and then it started to grow again. He wanted this idea that it’s a pocket universe, that you open this door, and you go to another dimension where you have an infinite amount of space. It was always gonna be somewhat visual effects. They built about the first two or three cabinets back and dressed them out with really interesting props, and then shot it on a blue screen. Two of the large overhead lights were built on the set, so that they had some justification for the practical lighting, but from there, it became a question of how to populate it all the way out.

It got into this interesting esoteric concept of what does a pocket dimension look like? So we started putting all sorts of different skies. We tried starfields, we tried to do something a little bit more fantastical, magical nebulas and nebulas on the horizon. We tried all these things — they all just made the plate look fake. You had this fantastical world behind this obvious thing that’s somewhat shot on stage. Somebody came up with the idea to just lean into the whole warehouse idea. One of the producers pitched the idea that we just put a bunch of white fluoro-lights overhead, just all these white light panels receding off into infinity. We were doing a lot of concept work at this point, and we thought it was a little bit of a silly idea. We tried it, and of course, it just instantly clicked into place. His idea was that when the door opens, the dimension kind of creates itself. It’s held in some sort of stasis, and it collapses back down to a singularity until it’s needed. When the door opens, you see all the cabinets sliding away from the door. They’re all squished [and] flattened so that they’re growing as they’re sliding out. Once you get into the room, all the rest of the cabinets are just slowly dropping from space, as if they’re materializing from overhead.

The guys came up with this really cool idea of how they shimmer into existence. The nice thing about the overhead fluoro-panels is that we just popped in those panels, one at a time, going off to the horizon. It gave us yet another way to tell everybody that the world was building itself. One of the biggest challenges we had was that you’re shooting a forest from ground level, and you’re trying to sell the concept that it’s an infinite forest, but all you’re seeing is the first four or five trees. That’s why we dropped the cabinets from overhead — because it became this visual language you’re trying to sell. How do we explain that this thing is continuing to grow, because, after one or two shots, you’re not gonna see anything happening if everything happens at ground level? That’s why the overhead lights became very important. That’s why dropping the cabinets from overhead became important. It’s just little fun things to figure out, as you’re trying to put the team together and hold on to an idea.

BTL: I get the impression from reading the notes that Weta did a lot on Peacemaker, but were you still working with other VFX houses?

Williams: There were other houses that worked on it. A lot of the process shots like car and apartment windows were done at other vendors, and I think a couple of things were done at other vendors. For the most part, we did a lot of the heavy CG work like the caterpillar cow, the butterflies. Some of the gore was done at other vendors, and they did a really good job.

BTL: Who makes the decision on how much Weta ends up doing? Is that James’ decision or Weta’s decision based on what you know you can get done in the required time frame?

Williams: It’s a little bit of both. Like I said, we had a good time on Suicide Squad, so James was keen for us to do as much as we could take on, and then it just comes down to a financial question of what makes the most sense. I like the work that we do here at Weta, but we’re not necessarily the cheapest company in the entire industry. Look, that makes it sound wrong, but the right choices were made for the right shots.

BTL: Does Weta end up spending as much time working on eight episodes of a series as it would on a two-hour movie?

Williams: We actually did more work on the eight episodes than we did on the entire [Suicide Squad] movie. Mark, do you remember how many shots we did on Suicide Squad?

Gee: I can’t remember. It was close to 600 or 700.

Williams: And then for Peacemaker, I think we did just over 800 shots, so it was just a little bit more work than Suicide Squad.

Gee: Smaller team and less timeframe, as well.

BTL: How does it end up being a smaller team? Is that just a budgetary consideration as well?

Gee: You’re dealing with TV, so it’s definitely a budget thing, but it worked really well. We basically had two main teams working on various sequences, and everyone was a bit of a jack of all trades and just really got into it, and it just worked really well. Whereas, in The Suicide Squad, there’s a lot more complexity in a lot of the shots, so we needed a broader team and especially with the FX department as well.

Williams: We didn’t have to destroy any cities from the ground up.

BTL: I’ve spoken to various people at Weta over the years, pretty much through the pandemic, and Weta quickly had a system in place, so at this point, are you all back in the offices now?

Williams: I miss everybody, because the world is still very heavily remote. Weta, to its testament, when the pandemic hit us during the beginning of post on Suicide Squad, they had to move 1,200 artists home over the course of a weekend, because the government just said we’re shut down. They did an amazing job of building an entire infrastructure in like two days and getting everybody settled and in their house safely. Since that, getting back into the office, we’re totally open for business where everybody that wants to come back is allowed to come back. Just like the rest of the world, we’re kind of in this interesting place where some people still choose to work from home. The process still holds, just like it did during the pandemic. We have good infrastructure. Even when we’re all in the same building now, we don’t do meetings in person anymore. We do them in a variety of little conference rooms going around the company using Teams. The process is still in place, and it’s still pretty robust, but it doesn’t mean that when I walk around in the morning, there are as many people here so it’s kind of lonely.

BTL: Does it make your jobs easier or harder, since you have to track down people who aren’t online?

Gee: It’s a bit of both, actually. It can be really challenging, but you can find people at all hours of the day, especially since we’re dealing with overseas people as well. We’ve got people in Vancouver. We’ve got people in LA, and we’ll soon have people in Melbourne, Australia as well. It’s almost like a 24/7 setup, really. In the core hours, we go into work and work our core hours, but overnight, you leave all the rendering and the lighting to all the other people overseas, and you come back in the morning, you got some fresh renders and more work. It kind of works well, but there are certainly limitations to it. I do like being collaborative with people within the same space and face-to-face, but it’s just the way it is these days.

BTL: Another thing I’ve spoken to other Weta people about is virtual production. ILM does a lot of stuff for Lucasfilm’s Star Wars shows using the volume. Has Weta started getting more into that realm as well, or are you mostly working in post to make stuff shot on the volume look better?

Williams: You’re touching on something that’s close and dear to my heart. I’ve been involved with virtual production since the beginning of virtual production. We started on the first [Lord of the] Rings movie. We gave Peter Jackson a virtual camera and had him shoot mo-cap with a virtual camera. Virtual production didn’t just happen in one day on one show. It got to this point around Avatar and Tintin time, where we realized we were doing all these films, using a lot more… the whole concept of virtual production, for Weta, at least, is bringing the digital component of post-production into the shoot. It’s collapsing the two paradigms together so that you leverage the strengths of both. Mo-cap, in itself, is sort of a virtual production paradigm, but extending the fact that you want the live-action camera represented as a digital camera during the shooting of the mo-cap, and the director can then walk around with a camera and lens what he’s shooting in the mo-cap. In the case of Lord of the Rings, he’s actually looking at the cave troll smashing around the room. As the guy’s performing it, [Peter] is walking around with a camera and figuring out the way he wants to shoot the shots.

Jump forward all the way to Avatar, where the idea was to completely meld the two worlds. That’s where the concept of the “virtual art department” came up, where you have an art department that behaves just like the art department on set, but it’s generating assets that are never built, but still cataloging them, doing all the research, doing all the design and artwork and then building it. It’s a very similar process – it’s just happening in a virtual realm. What’s interesting is that Jim [Cameron], coming from a practical background, wants to leverage the brilliance of the entire film industry, and not just say, “Practical production is dead. We’re going onto virtual production.” He drags both teams together, to the point where [in] the virtual art department, we had a wardrobe department that had seamstresses. Basically, we made actual versions of outfits, so that we can then create the digital version of [them], even though they’d never need to be made, because they’re never going to be shot, because avatars and Na’vi aren’t real. It was invaluable, because, for him, it gave him a chance to look at an eight or nine-foot tall maquette wearing an outfit and say, “I like that” or “change this, change that.” It gives you a lot more of a physical representation to it, but it also is great for the visual effects team, because we can look at it and go, “All right. This is how we’re going to build it.”

So, virtual production is something that’s been around for a bit of time. This new crop of virtual production or what we’re calling virtual production, it’s another evolution of it, using LED walls everywhere. LED walls are fantastic. They are really good for what they do, but you have to understand that LED walls are a very small part of the equation. What I mean by that is they’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of this session, but LED walls, the best way to think of it, is that they’re a fantastic translight. It’s something you can drop behind your action and do much more than a translight ever could. You can have people walking around back there and walking down into depth, so that you can make your set that looks infinitely large and not just have city lights twinkling on the horizon. It’s like the world’s uber-translight, but a virtual LED wall isn’t going to have a T-Rex come forward and bite someone. It doesn’t have the ability to interact. Simply, the LED wall, the way they work, you can’t really focus on them, so LED walls work best when they’re played as a background so that you can hold focus in the foreground, and let them go, even if it’s just a pixel or two out of focus. That’s enough to get rid of the artifacts. So, LED walls are fantastic, but it’s just one of those things. It’s one of many tools in a good virtual production pipeline. Just like any tool, you want to be careful, and you don’t want to overuse it. Practical effects are great, but you don’t want to try to do things that can’t be done in practical effects, just so you say you did them in practical effects. It’s all about trying to make the artist’s toolkit – the box of paints and brushes and pencils – trying to make it as diverse as possible, so that when it comes time to create something you have to That’s.

BTL: Production design and visual effects have been moving closer together, to the point where production designers can design something in a computer, and just hand the file over to VFX, who can use the file to build their assets. It’s pretty amazing where things are going, and everything is also looking better than ever.

Williams: Trust me, you can respect James Cameron for a lot of things, but it’s one of the things I respected the most is the fact that he sees the industry as a bunch of very talented people, not like these people on the out, these people on the in. He’s always trying to bring the best of the people together and bring the best tools to those people. He’s encouraging people to build stuff in the computer and build stuff practically. It’s about not losing skills, just because we change the tool. To that point, when I started in this industry a few 100 decades ago, I started a company called Boss Film Studios, a fantastic company. I loved working there with Richard Edlund, but when I started, they had just built a CG department. They had been a practical effects company for the longest time. We had blue screen stages, we had a working model shop, we had shooting stages, so it was this interesting time when we were transitioning from models and miniature effects and creature effects to digital effects. There was an animosity at that time, in the industry, because a lot of the people in the industry didn’t want these computer guys, all these kids, to come in and take over the industry.

The sad thing, to me, the thing that ripped at my heart, was all these incredibly talented people that despised us and didn’t want us to be there were kind of sealing their own fate. They didn’t have any desire to learn the new tools, but at the same time, some people did, like Michele Moen, this fantastic matte painter who’s been painting on glass for this incredibly long time. Unfortunately, it was the matte paint department with all the glass panels that had been conscripted and turned into the CG department, so she was out of a job, in essence, at least at that company. But every night I would see her just tilling away on the computer, teaching herself how to do stuff. The first project I had to work with her, they were like, ‘Hey, do you want to work with her on this project? She’s never done it before, but to help her out.’ She painted textures for a wooden sailing ship, and I can see every brushstroke. This doesn’t look like a photograph. It looks like something that’s painted. But the second, we textured the ship and put it in the shot, it looked perfect. She got every detail down, so it was at that moment that I realized that the worst thing this industry can do is to ever leave somebody behind, is to ever take an incredibly talented person and deprecate their job without trying to pull them in. If there is a great tool, pull them into the tool, encourage them to use the tool, or at least support them in not using the tool, but don’t lose their time. Like you’re saying, production designers that sculpt things in ZBrush now and pass over sculpted models to us, it makes our job so much easier. We can cut down that cycle of interpreting what they meant us to do, and actually, take their brilliant concept and execute it in a much more faithful kind of way. I’m very passionate about that.

Season 1 of Peacemaker is now available on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as streaming on HBO Max. And we’ll have more with Guy Williams soon, as we also spoke to him about his work on Marvel’s She-Hulk: Attorney at Law.