Chances are that if you’re into British music from the ‘80s or ‘90s, you would have heard some of Composer Adam Peters’ work, most notably on Echo and the Bunnymen’s classic album Ocean Rain, on which Peters played and did the string arrangements. That was quite some time ago, and a different chapter in Peters’ life, as he’s spent the last decade or so providing music for films and television series.

After doing quite a bit of work with Oliver Stone, Peters connected with filmmaker Bryan Fogel for his doc, Icarus. When that movie won the Oscar a few years back, it made perfect sense for the two to collaborate on Fogel’s latest doc, The Dissident.

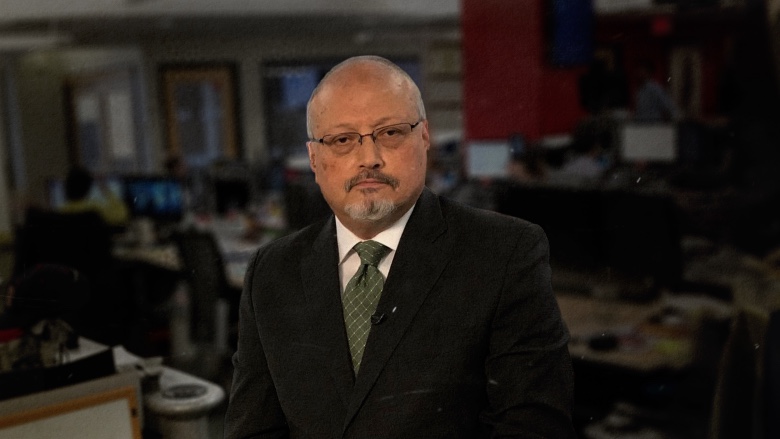

The film explores the killing of reporter Jamal Khashoggi while visiting the Saudi embassy in Turkey to get some paperwork for his impending marriage. The film plays out like a chilling thriller, as we watch Khashoggi entering the embassy of his free will never realizing that he wouldn’t be leaving. Fogel’s investigative style includes an in-depth look into the conditions in Saudi Arabia leading up to Khashoggi’s murder, as well as interviews with his fiancé. Peters’ ever-present bed of music helps build the tension in many of the more harrowing scenes from Fogel’s film.

Below the Line spoke with Peters over the phone a few weeks back for the following interview. (For the sake of transparency, the writer worked with Peters way back in a long-forgotten era known as the ‘90s. After a little bit of catching up, we got right into his background and process of writing music for film and television.)

BTL: I know you were working as a musician and producer throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, so what got you into scoring? Was Oliver Stone’s Savages the first one you did?

Adam Peters: I just wanted to start writing in a way that I always wanted to, which was with pictures and feelings in mind I’ve always had, sort of building soundscapes that sort of say something. I think I was always doing that when I was playing in these bands. I was always listening to the lyrics and trying to react to them somehow. So I moved out to LA, and I just didn’t really know anyone. I knew a few of leftover people from “band world,” but I didn’t really know anyone, then I bumped into someone somewhere randomly, and they said, “Oh, I’ve got a room. Do you want to come use the room at this place as your studio?” So I kind of did that. We were just having a kid, a baby, and I was like, “Okay, I have to sort of really, really focus on this to make it work.” I don’t think anything works if you sort of half do it. Sort of backtracking, that’s what prompted the move, and then randomly I met this woman that was an editor, and she was editing something for Oliver, and she said, “You want to be a composer. Give me some music,” and she cut it into the picture and showed it to Oliver. It was a documentary he was doing (South of the Border), and then Oliver just loved it. So I went in to see him, and I started working with him, and I really learned how editorial works, by sticking close with Oliver. I just learned a lot about moviemaking from him, then he started doing Savages, and I did that. At the same time, he was also doing this 10-part TV series on the history of 20th Century America. His office was just around the corner from where I was, so I would just go around there and sit in. He’d talk about stuff, and I’d watch him editing, and bring him around music, and I really just learned a lot from him.

BTL: This was around the early to mid-Aughts?

Peters: Yeah, it was round about then, and it was pretty great. I’d be sitting there, and he’d get two calls. It would be Val Kilmer on line one and Mikhail Gorbachev on line two. It was my sort of introduction to Hollywood. And then from there, people just started calling me. It was really the music — the music actually opened the doors. He heard the music, called me in. Other people started hearing the music, and just everything I’ve done has been one thing follows on from another. Hans Zimmer, they offered me a room at their studio, so I moved my studio down there for a couple of years. I was doing my own thing, and he has a big staff of writers and stuff like that, which I wasn’t that interested in. It was good to be around those people and sort of learn more about how the whole process works and working with directors and working to picture and the sort of technical side of it, so that was part of it. It took me seven or eight years to learn really how to do it until I sort of now feel that I’m able to write as myself, as it were, as opposed to trying to write film music. I’m actually finding it very satisfying to do this. It’s not like I’m not sitting down going, “Oh, I wish I could go off and go back to the world I came from.” I’m really pleased I did that when I did, and I’m really happy I’m doing this now. I see them both as just one’s a progression that came from the other.

BTL: I’ve spoken to a few composers over the past few months at this new place, and your story sounds very familiar with other ones I’ve heard where they scored one movie and then someone else sees that movie, likes the music, and it just goes on from there.

Peters: Except for a movie everyone hates.

BTL: That’s true. I’m a film critic also, and there are movies that I’ve hated which I love the music.

Peters: You know, a really successful score can be a score that most people don’t even notice.

BTL: It’s interesting you say that because I decided to re-watch The Dissident, but only really listening to the music and not watching the picture.

Peters: I really think it’s a very successful score, in as far as it gives an emotional pull to it without it being manipulative. I think that’s kind of what I was setting out to do with it.

BTL: How did you meet Bryan Fogel originally?

Peters: I met Bryan, because I had done Snowden with Oliver. Bryan was working on Icarus, and then as the Icarus story developed, he realized what was going on. He’d seen Snowden, and he loved the music, then he saw the parallels in Snowden and Grigory Rodchenkov, the guy that Icarus was built around, basically being a Russian whistleblower and a dissident. I did that with him, so again, I suppose it went back to the Oliver connection, but it was the spy thing with that.

BTL: Had he already been temping your music to Icarus when you first met him?

Peters: The first version that I saw of Icarus was about seven hours long. [laughs] You could have temped it with the entire Beethoven catalog, and it was about 8 films in it at the same time. The way you do it is that they temp it with whatever they want, and then you start giving them stuff that you think might be in the right area. I kind of like it when the temp is not that great, but where someone’s just grabbed the piece of music where they think it has the right sort of atmosphere. I can read that pretty well, talking to the editors now. If they’ve started cutting really deeply to the beat of the temp, then it can provide some issues that can be a little tricky to extricate. Once I came on board, they started temping with the Snowden stuff.

BTL: Are you generally writing to picture? I think I read that you were involved with The Dissident even before or as Bryan was shooting it.

Peters: Yeah, we talked about it, although the process was quite manic, because so much was unfolding so quickly. The way I normally like to write is I like to talk to the director, or whoever’s the main person, if it’s the director or the producer, whatever. In this case, it’s always Brian, but just talk to them and get a feel for what it is they see in the story and the characters. And then I’ll look at whatever – I’ll look at a picture or I’ll read articles, I’ll do some research. If there’s any rough footage, I’ll look at it, and then I’ll sort of turn that off, and then I try to write for at least a month where I just write and try and create a musical world that in my head is what I’ve gleaned from the conversations. If I can get to the heart of what a director is feeling — because the director hasn’t managed to articulate visually what they want in the early stages, so they’re talking about something that’s invisible. Music’s invisible as well, I suppose.

You sort of create this land that’s kind of similar to when I used to listen to music when I was really young, sort of lie on my bedroom floor with headphones on. I’d listen to these albums and they’d take me to all these places, and that’s the place that you want to go to when you’re writing, but it has to be the right place for those characters and that story. If you can create that place, and then you can play it to the director and the editor, and they can feel it with you, then you’re golden, then you’ve planted your field, as it were. As they’re making the picture, and all the changes happen and storylines change and edits change, you’re all pulling from the same well, as it were, musically.

BTL: It sounds very similar to what you might do if you’re arranging strings for an album where you create something and then have to make them feel that that’s right for their music.

Peters: Yeah, it has to be the right thing. You can’t bullsh*t this stuff, because it just doesn’t land. It has to be real, and it has to be right with the people I work with.

BTL: When you’re writing, do you sit at a piano or pick up the cello or what does that depend on?

Peters: No, there’s always a point in it where I will sit at a piano and just play around with melodies, and I might sit at the piano for a few days writing. That stuff normally doesn’t make it, but there’s a motor function that comes with it that it just sort of gets the juices going, and it stops me writing in… When I write on the computer, you can write in the same way, and when there’s computer or anything, no interface, apart from just a piano or a cello, you think in a different way. Quite often, I’ll take those ideas, and then they’ll inform the sketches that I make when I sit and write. I write in Pro Tools, actually. I don’t write a lot with MIDI stuff. I write with instruments, recording them, and then f*cking around with them.

BTL: A movie like The Dissident is literally two hours of non-stop music, so when you have all of these ideas, how are you able to fit them all in?

Peters: It kind of works that you have these anchor points. There’s always moments in the film where you’re really sort of showing who the character is or what the story is. Those are the main islands that you want to be landing on. Those are the sections that I try and write earlier in the process, and then getting from one place to the other, that’s normally a question of taking material you’ve already written, but then applying the sort of journeyman skill of composing, as opposed to the inspirational side of it. So it’s like how do you get from A to B? Oh, well, you have to go down this road, then you have to make a turn here. Then you go along there, you go through the trees for a second, then you come out into into a field with light in it. As long as you’ve got your field of light and the cave of darkness that you are in, sort of getting from one to the other, then yeah, I’ll take elements of it, and then you’re looking at the speed of the camerawork, the speed of the edits, the texture of the picture, all that kind of stuff.

BTL: A lot of this score is electronic, an even the strings are not the normal thing where you go to Abbey Road and record a huge orchestra. Was that a decision you made, or made with Bryan?

Peters: It is a decision I made. I knew that it was going to be changing really quickly. Picture was changing right up until the end of the process, and I knew that I was going to have to be writing fast, especially as the wheels start turning really quickly towards the end. We didn’t even get the transcripts from the Turkish Government until a few weeks before the final dub date. For this, I just felt it was going to be much better to keep everything under control and do it here. Also, I think when you’re making a documentary, it’s probably not appropriate, a hundred-piece orchestra, it’s just not the right sound. I mean, I’ve done that. I did all the orchestral cues on the first Paddington, and that was months of work at Air in London, and a lot of set-piece writing, and that WAS appropriate. But this, it’s different. It’s a more personal story. I also think that the electronic sort of side of things was the right sound for this, as well.

BTL: This played at Sundance, so was it actually finished and done before then?

Peters: I was really going around the clock for a couple of months to get this done for Sundance. I think the Sundance was in January, and we were still dubbing at Skywalker a week before Sundance. That was like the middle of January, we were still dubbing and changing things and all that. I was up there with a laptop and the music editor, and things were moving really, really fast. I don’t think we got the transcripts until the end of November or December, something like that. So suddenly there was this whole new line — stuff that we knew that had happened and was already incorporated in the story, but Brian hadn’t got the physical piece of paper from the Turkish authorities until then.

BTL: Was the Turkish government editing and approving what could be shared in the transcripts?

Peters: It’s the actual transcripts of the killing of Khasshoggi, the transcripts from the room of actually what happened. At one point, we thought we were going to get the audio.

BTL: Obviously, COVID and the pandemic has messed up a lot of things. I don’t know where you were with whatever project you were working on. Being a composer with a studio, it’s a little easier to get work done in some ways.

Peters: I’m very lucky in what I do, in regards to the pandemic. I’m in my studio, and I have a COVID protocol with my assistants. I’m sort of locked in my room writing. I have tried some of this remote recording stuff, and it doesn’t work great for me. If you’re the type of composer that writes a MIDI score, and then it’s done and it’s recorded. If that’s what your thing is, then I think it can work very well for that. I write my scores slightly differently. I don’t use much MIDI. A lot of it is about modulating the real time performance against the picture –I am constantly tweaking it and molding it until the performance feels right to me. I can’t do that with the remote recording. There are too many nuances, and I feel untethered from the musicians. I’m more like, “Hey, what can we do with this clarinet? Can we put this mic here? Can you blow, so it sounds like …” whatever. There’s how I get to the place where it feels right to me and the director.

BTL: It’s great talking to you again. You sound exactly the same even though you’re now in this completely other world.

Peters: Well, it keeps me feeling really vital. The same way I felt that when I was in my twenties, and my bands were vital and part of the bigger conversation. Now in the world of movies and Hollywood, I am always meeting intelligent and perceptive people who have energy, and they’re creating relevant things. Each project is a whole new story and set of characters that I get to spend time with. It’s brilliant. I really like that about this world.

You can watch Bryan Fogel’s The Dissident On Demand through Prime Video, Apple TV and other platforms — you can see the full list on the website.

All photos provided by Briarcliff Entertainment except where noted.