While the United States has more than its fair share of animation studios making big-budget CG feature films, France has long had a rich history for animation that’s often as much or more about the art as it is about the commerce.

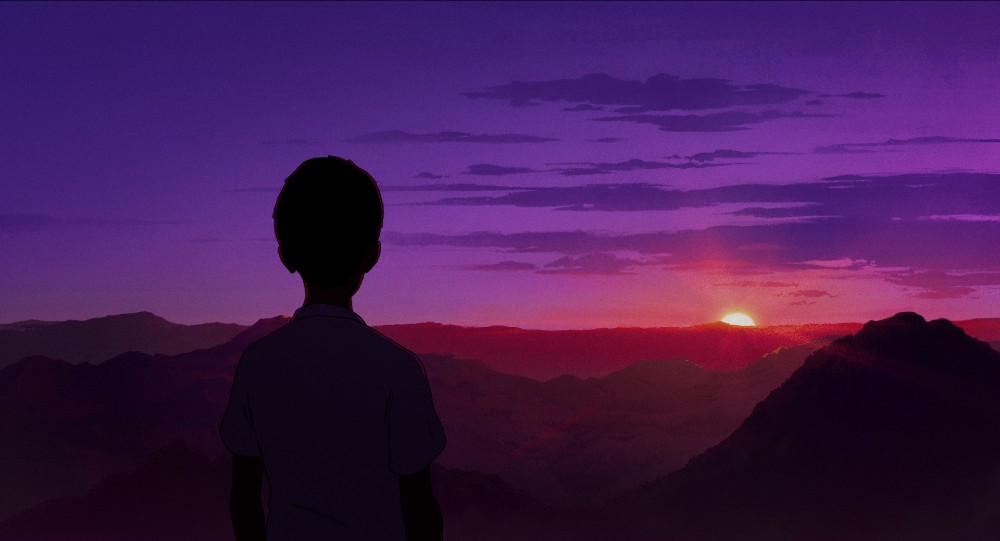

Patrick Imbert’s The Summit of the Gods is one of those great examples of how animation can be used to tell stories not necessarily for kids, using animation filmmaking to tell big epic stories that would require hundreds of millions of dollars if told via live-action.

The story begins in 1924 when George Mallory and his companion Andrew Irvine are reported to be the first men to scale Mount Everest. A Kodak camera they took with them could show whether or not they actually reached the summit, something Japanese reporter Fukumachi Makoto becomes fascinated by 70 years later when he sees what could only be Mallory’s camera in a picture of an enigmatic mountain climber named Habu Jôji, believed to have gone missing years earlier. Convinced he has an important story, Makoto goes looking for Joji and the camera and ends up going on his own treacherous journey to climb Everest to find answers.

Based on the Manga series by Jirô Taniguchi and Baku Yumemakura, which was based on the latter’s novel, Imbert along with his co-writer and producer Jean-Charles Ostorero has successfully brought this story to the screen using gorgeous 2D animation techniques that could very well have come from Japan, another country where animation has been defined.

Previous to Summit, Imbert worked in the animation department for the Oscar-nominated Ernest and Clementine, and then directed a segment for The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales, which received a number of Annie nominations, as well as won the Annecy International Animated Film Festival award for Best French Film.

Below the Line got on Zoom with the French filmmaker when he was in New York a few weeks back for the following interview. [Note: English is not Imbert’s first language, so we did the best we can to keep the original intentions in Imbert’s responses even when not always grammatically correct.]

Below the Line: This is very different from Big Bad Fox and some of the other things you’ve done, so how did you discover the source material? I guess there was a manga and a series of books?

Patrick Imbert: The very first book, the novel, had been published in Japan, but it didn’t go out [to other countries], so nobody knew it. We only knew the manga, and I knew Taniguchi’s work quite well, but not this one, particularly, before I discovered it. At that time, I was working on the Big Bad Fox at Folivari Studios, and it was proposed [I] do a few sketches on character design at that time. It was only a few days work. I had read the manga for professional purposes, of course. I didn’t open it before, because it’s about mountains, and that was not my interest, so I never had the idea to read the manga before it was offered to do this. But I was wrong, because once I opened this, I could not close it again. It’s a great, great story, and I love it, so this is the way I discovered the story.

BTL: It’s good timing because there’s a lot of interest in mountain climbing from movies like Free Solo, and The Dawn Wall, and The Alpinist, all these great documentaries.

Imbert: I discovered that this was a whole universe, the passion for mountain climbing is such a big world.

BTL: Because you weren’t into mountain-climbing, what was it about the manga that captured your interest? Was it just an interesting piece of history to explore?

Imbert: I have to say that this is common in this country, it’s very well-taught, and whatever Taniguchi is doing, it’s always good. Even just a man walking or a man eating, there is no story, but still, I love it. On the Summit of the Gods, I loved the way it is told, and I found something that was so universal. A lot of themes in the manga include the question of why we do the things we do? This is the theme that echoed in me, and this is the axis I wanted to use for the movie.

BTL: It’s a rather complex story, because it covers different timelines and characters. When you decided to adapt it, was it hard to figure out what the focus should be and what to keep in and take out?

Imbert: I thought the most important part was these two characters’ paths, so the first choice was quite easy for me. Still, that doesn’t make a script, so you have to test the idea basically against the reality. When you are a director, you definitely have to know what you are talking about, and what you want to say. This is a kind of guideline, let’s say a railroad, on which you put the movie, you see, and whatever you choose to show, to draw, it has to be on this railroad. After the main idea, it’s really a long and tough job to build it.

BTL: Was Netflix involved fairly early on or did you do it at another studio, finish it, and then it went to Netflix?

Imbert: No, no, Netflix came at the end of the production. Maybe the distributor was in the situation. Maybe they were talking to Netflix before, but I don’t know anything about this. It’s a separated world. This movie is made by a very small producer, and I didn’t hear about Netflix before a few months at the end.

BTL: How much did the art from the manga influence the animation style you’re going to use?

Imbert: Not that much. Taniguchi’s point of view influenced me a lot, but I didn’t feel obliged to copy his style. I didn’t do it. It’s realism, so I did realism, even on to my own tastes. The main interest of Taniguchi is not in the drawing in itself. He does great composition, that’s true, but the drawing, in my mind, is not the most important. I used some of the compositions and certain frames from the comics that gave me a few ideas for some scenes in the movie, that’s all. I always try to think about how Taniguchi will do [something] in my mind and not only specifically with The Summit of the Gods, but also with the other mangas [of his] that I read.

BTL: Mountain climbing is a very active sport, and it’s very specific, involving meticulous movements and timing. How did you and your animators learn how to recreate those movements? Did you have any specific reference?

Imbert: We had so many references, and thankfully, on the internet, you have so, so many movies and photos, so we used it a lot, because none of us were climbers. Some of them climb rocks [and do parkour] but that’s all. Snow climbing is very technical. We also had to have some consultants — one of them is a Summiter. That means he’s a guy who reached the summit of Everest, and we also had someone that came in the studio with all the material, the equipment, and showed us how to do knots. At that time, we took many pictures of him, and it helped a lot to animate everything.

BTL: Did you work from photos and other references for the look of Mount Everest, as well?

Imbert: We had many, because this place does exist, and since I respect my subject, I want to treat it well, so we have many photos, but it was only a base. The goal of the movie is not to depict Everest, it’s not a documentary. We have to give the audience some feelings, emotions, but I didn’t want to just describe it. So first, we had to be based on photos and know what we have to do, but there’s a lot of work [to create] the atmosphere, about the light, about the composition. A big part of this job was in the color script stage, so it took a long time. The artist who made the color script is also a director in animation shorts, and we both love the live-action movies and photos, so our influences were not animation. Sometimes in the Ghibli movies, the blue sky is blue, the green trees are green, but this is not what we wanted to do. We tried to have the most cinematic approach as possible.

BTL: You mentioned not wanting to make a documentary, but was this based on a real story, this climb between Joji and Fukamachi based on something that really happened? Or is that all fictional?

Imbert: The 1924 story is real, and the other characters in the novel are also a bit based on some real Japanese alpinists. In alpinism, the stories are always the same. I mean, it’s always a question about obsession, competition, failure, death, fingers cut, it always happens.

BTL: I wanted to follow up on an earlier question. You mentioned having mountain climbers coming to the studio to show the animators things, but mountain climbing has changed a lot since 1924, so how did you know what to keep from the old vs. the new?

Imbert: The consultant helped us a lot with this, because if you go on the internet, you can get a lot of documentation, but you don’t know when these types of harnesses [were introduced]. I learned, for example, that in the early 60s, the harness was just a belt. We were told by one of our consultants, he said, “Be careful, guys. This is not the same in the ’60s than in the ’90s,” so yes, he helped us a lot. There is also a shop in France very famous for camping and mountain stuff, called Au Vieux Campeur, and it’s existed for many years, so they have archive catalogs, so it was funny to see the stuff from different years.

BTL: I asked before about figuring out what to keep in the movie and what to take out. I also want to ask about pacing. Getting to Everest is gonna be a huge moment in the movie, so how do you decide how much set-up to do before you get to that moment? (NOTE: Spoiler Warning in Imbert’s response.)

Imbert: First, you’re right. Pacing is definitely important for me. Pacing is making a move — it’s key. The movie is built on progression, and I thought that if it was only mountain scenes, maybe it would not work good enough. SPOILER Let’s take an example: Abu dies, but I want the audience to have empathy with Abu and be sad [about] this. If you want to have this, you have to build a relationship between the audience and the character before. I needed to create this dialogue, since I’m in the first part of the movie. In my mind, it is absolutely a necessity before going up, before the adventure. You cannot separate this, I think, and also I like the psychological side of the story. This is what I like in Taniguchi’s work, so I tried to put it in the movie.

Quite early, it appears that the Everest sequence will take place maybe not [at] the [halfway point], but maybe a little less than half. It actually happens like this. Even if it changed a lot during the animatic process, the balance between the town and the mountain is more or less the same. It’s pleasant to watch it, but I love character scenes, because I love characters. If you don’t have interesting characters, you don’t have any story. Regarding Habu’s story, I wanted to show all the obstacles that he encountered. It’s about competition, failure, because his arch-rival is better than him, and it’s about heroes, lack of money. So he cannot do what he wants to do. So all of these problems are interesting to show. If everything goes well, for a character that is not interesting, you see. So, I thought it was quite interesting that I’m interested.

BTL: How did you find Amine Bouhafa to do the music for this? Because the score is absolutely gorgeous.

Imbert: The producer proposed me to work with him. I didn’t know him, and if you don’t know him, either, I think you will in the future. He’s really an incredible composer, and he will be a big star soon, I think. It happened like this. I met him and it immediately clicked between the two of us, because he first heard about what I wanted to do, and he didn’t want to propose to me any melody first. He worked on a kind of toolbox. He built some sounds first, and then he asked me, “Does it sounds good to you? Do you feel any mountain impression?” I said yes or no, and with this, he later started to work on the melody and the composition in itself. It was a very big help for me, because music is a big part of the narrative work. He always asked me, “What do you want to say in this scene?” Most times, I knew, of course, but sometimes, I was surprised that even I did not know exactly what I wanted to say, and so, it helped me to define it precisely. It was a really important collaboration that we had between us.

BTL: Do you record a lot of the voices or any of the narration before animating?

Imbert: Yes, we always do it before. Always, always.

BTL: Do you end up doing the narration and dialogue in different languages, too?

Imbert: No. Sometimes people ask me about this question of languages and [doing the movie in] French. It’s kind of weird for English-speaking audiences, I know this, but I didn’t expect that the American audience see it in French. It happened because Netflix didn’t have time to dub it. I just work in French, because I’m French, and it’s easier for me to write and to understand what the people say, that’s all. It’s just my language, but definitely, it’s supposed to be dubbed for each audience’s language, and I do want that the language is close to the audience. I want it to be familiar.

BTL: When you were making this movie, what was the biggest team of animators or artists did you have at one time?

Imbert: I’m sorry, but it’s difficult to answer, because we had more than 100 people, but all the steps are at different times, and some are working on the first step, let’s say layout or posing, and then, the animators make the things move, so it’s another step that takes a very long time, and then the color and then compositing. They don’t work all at the same time, and I don’t even know how many people. I’m sorry. A lot. Of course, it’s much less than the big US productions, but it’s quite a lot.

BTL: My last question is a bit general, but how is the animation business in France? It’s a country with a long history of animation, so how is it doing now and how has it handled COVID and working from home, etc?

Imbert: COVID didn’t have a lot of impact on animation, because everybody can work at home. It’s too bad, because you cannot see your friends at coffee time, that’s all, but it’s working. Globally, I think it is a good period for animation, because there’s a lot of work to do. As there are more and more screens to fill and more platforms and more channels, there’s a real request now for animation for all these platforms. This is just my point of view, but I think the industry is good, too. The talent can only grow in the industry ground. If you have no industry, it’s very difficult to have some artists take off and bloom. As there is a lot of work, sometimes you have really great artists that happen, so I think it’s a good period.

BTL: I’m not sure if it’s the case over there, but here in America, many kids are getting into doing animation since they can do it on their iPads. Is that the case in France as well?

Imbert: I think it’s the same everywhere in the world now. Maybe not everywhere, but in France, it is.

Summit of the Gods will be streaming on Netflix starting Tuesday, November 29.

All photos courtesy and copyright Netflix.